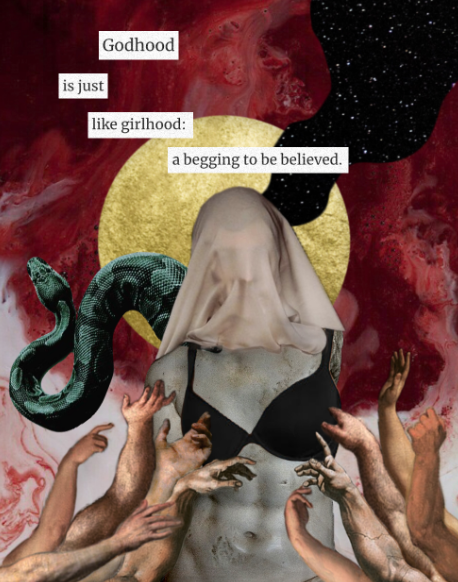

In the piece “A Modern-Day Cassandra,” Annie Ma depicts a twist on the Greek myth of Cassandra, a girl cursed to utter true prophecies that no one believed.

‘Well, What Did You Expect to Happen?’: The Backlash After Sexual Assault

All students who shared personal stories in this article have been given pseudonyms to protect their anonymity and privacy.

Bianca was in Seattle when it happened.

“This last summer, I was at my friend Sadie’s house – she lives in Seattle with her now-boyfriend and his best friend,” Bianca said. The four of them were hanging out together. “Throughout the night, things started happening, and I was kind of getting cuddly with [the boyfriend’s best friend]. And then I got really tired, so I went to sleep.”

In the middle of the night, Bianca woke up. “I’m on fluoxetine and fluoxetine can make you have really vivid dreams. First of all, let’s just say that,” Bianca said. “So, during the night I woke up and I like – I don’t know what happened exactly, but I know that my pants were off in the morning and my clothes were scattered all over the floor. And I remember waking up and him having sex with me and I thought it was a dream, so I went back to bed. Like, I fell back asleep. And then that morning, I woke up and my pants were gone.”

Bianca ran upstairs and found Sadie with her boyfriend. Bianca explained what had just happened, but Sadie brushed her off, saying, “Well, he wouldn’t do that. He’s a nice guy.” Sadie also told Bianca, “Well, maybe it was your meds. Maybe it was a dream.”

Bianca didn’t think it was a dream; she’d never had dreams like that before. Still, Bianca said, “I was like, ‘Okay, whatever. You think it’s a dream. That’s fine.’ So I dropped it, and I’ve just been sitting on it, cause I don’t know exactly if it happened so I can’t really, like – I didn’t really want to go to anybody.”

Then, a couple of weeks ago, the man – who Bianca revealed was 20 years old – reached out to Bianca to see how she was doing. Bianca asked him what happened at Sadie’s house. He told her that they only cuddled and kissed. Bianca kept pushing, asking why her pants were off when she woke up. He kept telling her that he didn’t know. Bianca told him, “No, I don’t understand, because I fell asleep with my pants on and I woke up with them off, so that period of time I was asleep, something must’ve happened.”

The man kept avoiding her questions, so Bianca eventually stopped asking. “There’s not anything you can really say at that point except be like, ‘I think you raped me,’” Bianca said. “That’s really aggressive. And I’m not that kind of person.”

It was difficult for Bianca to process this event. “Before any of this happened, he was so nice. Like, he’s very kind, and he’s very polite,” she said. “My view of people has changed a lot now. Because like this person who was seemingly so . . . respectful – if he could do something so horrible, like, other people could as well.”

Like Bianca, so many survivors of sexual assault never share their stories. The reasons are endless – fear of retaliation, doubt that it really happened, shame, stigma, a lack of a support network – but the cycle is the same. Survivors of sexual assault who choose to share their stories often face ridicule, criticism, and backlash. Knowing that they could face similar consequences, silent survivors are afraid to share their stories.

Backlash when survivors share stories is a critical component of rape culture. It highlights the way that society focuses the dialogue of sexual assault on the behaviors and actions of the victim instead of the perpetrator, which inherently leads to the idea that the victim is at fault for the sexual assault.

This pattern can be seen in many forms. According to Vox, “The classic example is when an observer (or a rapist) blames the rape victim for attracting the rapist’s attention by wearing revealing clothing. In 2011, for instance, a Toronto police officer sparked the global ‘Slutwalk’ protest movement when he told female students that ‘women should avoid dressing like sluts in order not to be victimized.’”

This pattern can also be seen within the Middleton community. “I told [a kid from Memorial] about something that had previously happened, and he goes, ‘Well, what did you expect to happen?’” Skyler said. “He’s like, ‘You act kind of provocatively at times, and you speak your mind all the time, and you make inappropriate jokes and stuff.’ And he’s like, ‘And take a look at the way you dress and stuff. You wear crop tops.’ And I was like, so you’re saying that this happened because of the way I dress. And he’s like, ‘Well, not saying that you were asking for it, but you were setting yourself up for it.”

Skyler said that this has also occurred with Middleton students. “I noticed that happens a lot at Middleton too, like, there’s certain people that I’ve definitely told and they’re like, ‘Well, you shouldn’t have worn that.’ Me wearing a crop top isn’t me asking for anyone to ask me stuff, or try to pressure me into doing things,” she said.

Lindsay also faced backlash from her peers when she shared her story. Lindsay was sexually assaulted by her boyfriend when she attended a party. The assault happened while she was sleeping next to him.

“And it was difficult, too, because it was while we were dating, so that’s a big thing,” she said. “Sexual assault isn’t always this thing that comes from unknown people. It comes from people who you know and are intimate to, and that’s what makes it scary: because it’s people you think you can trust.”

Lindsay broke up with her boyfriend after the party. When she told their shared friend group what had happened, many of her friends sided with him. “[It felt like they were] telling me that this kind of thing, this simple, very obvious thing, that was occurring – basically, [they were] telling me that it doesn’t matter. And it was like, ‘We don’t believe you,’ but really it was just that ‘you don’t matter,’” Lindsay said.

“The fact that I said to them that I was abused, and nobody cared – it made me never tell anybody about that assault. And that’s what sucked. It kind of like tied this shame to it. It’s like, wait, if nobody believes me, am I just . . . crazy that this actually happened? It’s like they kind of stole my reality and my experiences from me by just being a force of people who I trusted and basically [telling] me that I was full of shit.”

According to the Rape, Abuse, and Incest National Network (RAINN), only 230 out of every 1,000 sexual assaults are reported to the police. That means about 3 out of 4 sexual assaults go unreported.

Colin’s experience falls in that 75%. “I was in a relationship with a person, and we both decided we were okay with having sex. I thought I was ready and then I realized I wasn’t,” he said. Colin told his partner that he was feeling a little depressed lately and unsure about having sex. “They told me, ‘Well, this will make you feel better.’”

Colin continued to ask his partner to stop and asked if they could kiss for a little bit. “We’d kiss, but they’d decided when we’d continue,” Colin said. “I thought I was fine because I was unsure, so it was okay, right? The more I let it sit with me, the more I realized it was wrong and not okay. I didn’t feel traumatized or unsafe with them after the experience, but everything felt wrong once I let myself process it rather than suppress it. I know it was never meant to be intentionally to hurt me. I know they are a good person. So I can’t hate them, but I still go into a panic when I think about the experience.”

Colin never reported the incident to anyone. “I felt like no one would believe me and I felt like because it wasn’t as extreme as others, it wasn’t enough to report,” he said.

The negative reactions these students either witnessed or experienced is shared with survivors of sexual assault and harassment all across the nation. In America, millions of women took to social media platforms, most notably Twitter, with the hashtag #WhyIDidntReport in the wake of Dr. Christine Blasey Ford’s testimony against then-Supreme Court nominee Brett Kavanaugh. They shared the reasons why they didn’t report when they were sexually harassed or assaulted – shame, guilt, feeling like it was their fault, etc. The movement dominated headlines for days and shed light on elements of rape culture that the famous #MeToo movement, almost a year earlier, did not explicitly address.

In the past three articles, we have heard the student perspective of rape culture at MHS. We have heard stories about rape jokes and sexual comments, upskirting and nude photos, sexual assault and the backlash of speaking out.

But students are not the only members of the MHS community contributing to this issue. The administration at Middleton High School also plays a role in perpetuating rape culture.

In our next article, The Cardinal Chronicle will look at the administration’s legal boundaries in dealing with sexual harassment and assault at school and reveal students’ opinions on how the administration handles the situation.