Worry, Community, Insulin: Living with Type 1 Diabetes at MHS

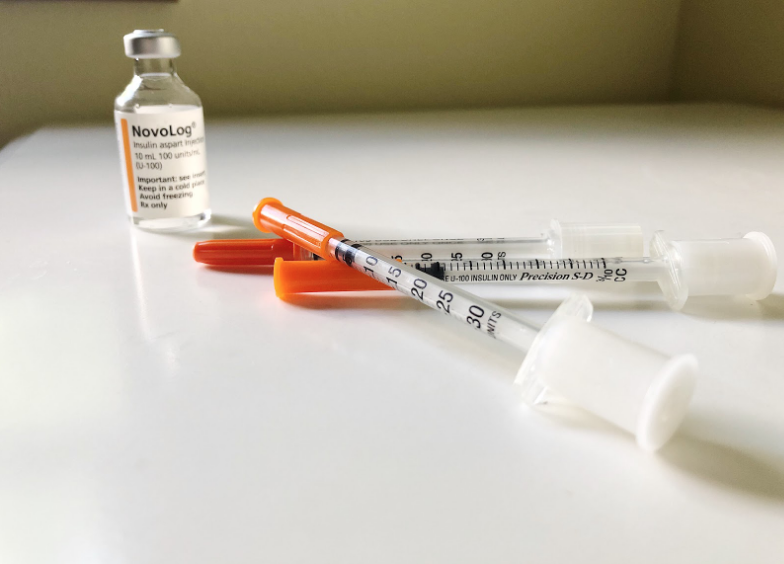

Novolog, a company that produces synthetic insulin for diabetics, costs about $311 per 10 milliliters of insulin.

In my lifetime, I have endured approximately 45,167 needles. Before I switched to a device called a pump, which administers insulin, I had bruises all down my arms from insulin shots. In elementary school, I was the only kid with Type 1 diabetes, although many students assured me that I wasn’t the only one because both their cat and their grandpa had diabetes as well – however, most likely not Type 1 diabetes. As a kid, I felt starved of understanding because I was virtually alone in my struggle with this autoimmune disease.

While my exposure to the diabetic community was very limited, according to the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), around 1.25 million Americans have Type 1 diabetes. Moreover, according to Beyond Type 1, 5 million people are expected to be diagnosed with Type 1 diabetes by 2050.

Mayo Clinic defines Type 1 diabetes as “a chronic condition in which the pancreas produces little or no insulin. Insulin is a hormone needed to allow sugar (glucose) to enter cells to produce energy.” In layman’s terms, the body attacks its own insulin supply, forcing people with Type 1 diabetes to seek synthetic insulin. Many individuals with Type 1 diabetes use insulin shots or devices called pumps, which can determine the corresponding amount of insulin needed for food or correct a high blood sugar through the administration of insulin.

Experts speculate that the autoimmune disease is caused by a combination of genetics and an environmental stimulus – illness or trauma – that triggers the disease. Type 1 diabetes, although incurable, continues to be researched as many devote their lives to finding a cure.

Type 1 diabetes used to be a death sentence up until the late 20th century, but it has become manageable through the use of technology. However, the companies creating the drugs and supplies that keep Type 1 diabetics alive have always seen their customers as money-making profits. According to the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), insulin prices tripled from 2002 to 2013. In 2017, the death of Alec Raeshawn Smith – a young adult who rationed his insulin because he could not afford supplies – led to the public labeling high insulin prices a crisis.

Although I am now surrounded by a community of people who understand my daily struggles, I have always been curious about what other Type 1 diabetics endure. To understand the experiences of other students like me, I took to the halls of Middleton High School to track down my fellow Type 1 diabetics to hear about their past experiences and to find if they, like me, worry about access to medication, maintaining their health, and access to supportive insurance.

Cara Davis, freshman

Although having Type 1 diabetes for only 4 years, Cara is quite self-sufficient in handling her needs; She checks her own blood sugars, changes her pump sites, and overall maintains her health.

Cara Davis was diagnosed in the early morning hours of April 6th, 2014. “I thought it was a dream because I was sick. I didn’t believe that it was real until the next morning and I was still in the hospital, and I still had the annoying IVs in my arms,” Cara says. In contrast to the setting of the quiet library, Cara is extremely expressive and loud; Her voice rose and fell as she told her story – to the whole library, it seemed. Despite the severity of the topic, Cara enthusiastically says, “And then it hit me: I’m diagnosed with diabetes!”

Although the injections and doctors appointments are difficult in the moment, Cara recognizes a more enduring struggle in the stereotyping of diabetes. “When you say the word diabetic, you think [of] a person who has eaten too much sugar or someone who is obese. You think of stereotypical Type 2 diabetes, instead of the genetic Type 1 diabetes,” Cara says in a drone as if she has already said this to dozens of people. With the rising obesity rates in the United States, Heart Disease, Type 2 diabetes, and Cancer have received rapt attention due to the correlation they have with obesity. Therefore, our association with diabetes has often been in conjunction with obesity. According to the Center for Disease Control says that over 30.3 million Americans have Type 2 diabetes.

Cara, who was diagnosed in middle school, says that the hardest challenge is feeling stuck with diabetes – “getting mad and feeling like it’s spiraling,” she says. Her once bubbly demeanor diminishes as she recalls her hardships: “[It’s hard] getting stuck in the spiral of chasing blood sugars and it not working and it just feels stacked against you and the hopelessness you get with that.”

The struggles of diabetes are only one facet of the disease, and nurses, friends, and mentors have had a positive impact on Cara. “I have only had diabetes through middle school and high school, but I’ve had really positive experiences with all of the school nurses,” she says. As Cara transitioned into high school, she handled more of her diabetes herself, going from visiting the middle school nurse multiple times a day to only visiting the high school nurse if she has a problem. “That shift has allowed me to grow more confident, because now I can trust myself in doing what I know is best,” she says.

As the number of people with Type 1 diabetes grows, technological advancements have helped make the disease more manageable. Cara cites Dexcom, a tool that tracks blood sugars, as a step in the right direction. “Being able to have my numbers pulled up on my phone and the improving pumps have definitely . . . made it a lot easier to manage my diabetes,” Cara says.

Despite the improving technology, Cara argues that there should be more discussion around diseases like diabetes. “Especially since I have Type 1 diabetes, I realize how undereducated people are,” she says.

When asked about her plans for the future, Cara admits that diabetes has influenced her career path. “I actually want to move to Canada because I can apply for Canadian citizenship due to my family living there. Their healthcare is free, so it would be a lot easier for me to gain access to all of the supplies that I need,” Cara says. “[Having bad insurance] . . . is a really scary reality because things, without having good insurance, can be really expensive, and I want to go into art, or graphic design, or digital art, but that can be really hard to make money in.”

Aidan McLeod, junior

Aidan McLeod, who is active in many activities in school, first struggled in elementary school to adjust to a different schedule than his classmates.

Aidan McLeod was diagnosed when he was two years old.

While growing up with Type 1 diabetes for most of his life, Aidan says, “I feel like one of the biggest challenges was in elementary school adapting to a different schedule than my peers.” Aidan’s quiet and concise responses gave the aura of discomfort – as if he hasn’t talked about this topic often.

He sits ramrod straight in the wooden library chair, but smiles as he recalls, “I remember when I was a little kid at baseball practices having to have a pump and a bunch of extra stuff in [my] bag. I still have a lot of extra stuff in my bag, like snacks. Things like that, having to interrupt your activities to go take care of it – that’s a challenge.”

Aidan has also run into some stereotypes about the disease, often related to sugar.“One time, one person thought I couldn’t eat popcorn. It was the weirdest thing. Either people think you need sugar all of the time or you just can’t have it at all,” he says, laughing slightly.

He acknowledges anxiety over what the future may bring. “I have thought about those first years after college and how worrisome they will be. I’m not sure I’m completely ready to abandon my parents, in terms of paying for medications and everything. Especially based on how ridiculous the upcharge is. Insurance companies nowadays can do whatever they want, pretty much, with things like insulin.”

Still, Aidan mentions, diabetes is not entirely negative, highlighting the friendships he has formed due to the disease. “I feel like I’ve met a lot of people at camp and especially with programs like that. It’s like another community of people,” he says.

With the bombardment of organizations asking for money and the scandals of reputable organizations misusing funds, Aidan recognizes the skepticism of organizations in supposed need. For example, the Red Cross has come under scrutiny as to how they divide their funds, along with four cancer organizations who were shut down in 2015 due to corruption.

As Aidan began to talk about his brother’s work, his expression relaxed and his voice became passionate, “We need more money for research, and everyone thinks, ‘where is that money going,’ but honestly, it really is going to research. My brother actually is in stem cell research right now. He has dedicated his post-college career to working for research for Juvenile diabetes.”

Aidan wishes that people would treat him the same as everyone else, saying, “We are just people too. We can function just like everyone else, in . . . pretty much all daily aspects of life. It shouldn’t affect anyone else negatively.”

Phoebe Miller, senior

Phoebe Miller has had Type 1 diabetes for more than two years now. She is very hopeful for an artificial pancreas both for herself and future children to come.

Phoebe Miller was diagnosed in January 2017, when she was a sophomore in high school. “[Type 1 diabetes] was very hard for me because I was a teenager. I had grown up without this hindering me, and then I had to completely adjust to it. I don’t’ think most teenagers have to go through something like that – such a huge life change,” she says. Phoebe’s diagnosis is somewhat uncommon for Juvenile diabetes. According to Endocrine Web, the peak age of a Type 1 diagnosis is 14 years old.

Phoebe recalls that when she was first diagnosed, she “was really close to the old nurses. They were very welcoming and actually, every day at lunch I would go into their office, and they would help me count my carbs for my lunch before I ate.”

Phoebe, like all other diabetics, counts carbs to make up for the lack of insulin in her body. Insulin is what allows glucose to enter cells, so, Type 1 diabetics must count their carbs to administer the correct amount of insulin. Giving too much insulin can cause blood sugars to go low, and in the worst cases, have a fatal seizure; conversely, giving too little insulin can cause diabetics to enter ketoacidosis – a possibly fatal state where there is an insufficient amount of insulin to fuel cells.

Phoebe says that she has changed a lot since being diagnosed. “ [Type 1 diabetes] is always on the back of my mind. I do plays; I have a fear like ‘What if I’m going too low?’ Or ‘what if my pump starts beeping?’,” she says, staring into space with a distressed look. “Also, during tests [like] the ACT, I don’t know if I can pull out my supplies. The test can be taken away from me, so I’m always thinking about it. I can never look at food again without counting carbs.” Phoebe speaks very slowly, and she puts emphasis on the bad parts of her experience. She often glances away as she speaks, with a glassy look in her eyes.

The strain of Type 1 diabetes, Phoebe says, has not been entirely negative.“I’ve gotten to know some really cool people. I’ve also become much more interested in endocrinology myself. I can see that being a potential career in my future,” she says.

As for her future, Phoebe adds, “My plan is to do pre-med and eventually become a doctor so that it’s ensured that my coverage plans are really good. Maybe not even that, but something just in the medical field so that I know I have good insurance. Which is such a sad thing to think about. Because what if I wanted to continue my acting career? I know how poor a lot of actors are when they begin and the thought of not having good insurance, because of my diabetes, is very scary to me.”

Phoebe continues with certainty, “When I tell people I have diabetes, I wish that they knew how much of a burden it is to have Type 1 diabetes and that in pretty much everything that I do, every step I take in a day, there is not a way to get diabetes out of my mind. I know that’s the way it is for a lot of other people. It’s for our own safety, we are thinking about it.”

The fight to cure Type 1 diabetes is not over. We can all help end the disease that afflicts 1.25 million people in the United States, whether supporting a Type 1 diabetic individual or donating to research.

Donate to the American Diabetes Association or the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation