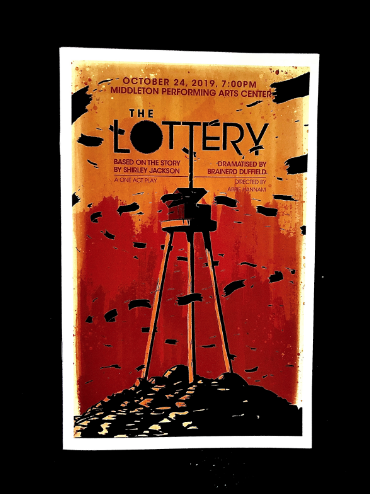

Review: MHS’ The Lottery

This year’s fall one-act play was The Lottery, a play based on Shirley Jackson’s 1948 short story.

November 9, 2019

On October 24, 2019, the Middleton High School (MHS) Theatre put on a public production of this year’s fall one-act, The Lottery. The play is based on the internationally-recognized short story by Shirley Jackson and dramatized by Brainerd Duffield. As the name would suggest, it depicts a lottery, in which the person whose name is drawn gets stoned to death.

MHS’ performance of The Lottery was noteworthy for many reasons. The blocking of the play, as well as the special effects, brought out many of the key thematic elements of Jackson’s work. The children placed in every scene as focal points in the background demonstrated the story’s theme with subtlety, showing the most innocent members of society participating in something horrible.

As a one-act, the buildup to the play’s climax must be rapid and expert to be impactful in such a short amount of time. Facilitated by the subtle and masterful body language of the cast and the shifts in atmospheric music, the play was tension throughout, climbing to the point where Tess Hutchinson is mobbed by her friends and neighbors and stoned to death. The scene fell on a chilling scream, leaving the audience with an unsettled feeling in their stomachs. That is where the play should have ended.

The acting, blocking, and performance of the play were expert and persuasive, yet I left feeling underwhelmed. The original story and play end on the image of Tess Hutchinson stoned to death. It is a poignant and sickening moment in time. When presented as the final scene in the play, it leaves the audience with unresolved grief and horror. That horror is vital. It provokes thought and allows the message of the story to hit with its full impact.

The MHS Theatre’s performance added an extra scene. When the lights fade back on, Bill and Davy Hutchinson remain on stage to grieve their loss. Instead of ending on Tess’ final scream, the play ended with Bill carrying Tess off-stage. It was a sweet moment, but given The Lottery’s trajectory and intention as a story, it did not make sense. The added scene depresses the emotional effect built by the rest of the play. Instead of ending on a chilling moment of reflection, the conflict and tension of the play are packaged into the story of a grieving family, not a commentary on the worst reflections of humanity.

While choosing the play, director Abbie Hannam asked herself how to handle what she perceived as “such serious and traumatic material.” For some, this was easier, but for actors such as Chase Harless (Bill Hutchinson), the tears seen in the moments of his classmate’s death were genuine.

Hanna Brachman (Tommy Dunbar) admitted that it was “tough being in the emotional experience of the show.”

As such, it makes sense that MHS Theatre took mental health into consideration, but it fails to explain the divergence from the source material.

There is a legitimate question in art of when the author’s intent ends, and the artist’s agency begins. When the author has failed to specify their intent, does that then make it okay for a director to edit their work? There are times when plays are edited for issues of concision or clarity, but neither of these were the case. If the extra scene was to lighten the emotional impact, it failed. Art like The Lottery exists to make us uncomfortable and to alter its message simply out of a concern that it may be difficult to watch or perform robs the integrity of the performance.

The Lottery is provocative and filled with emotions that are hard to process. That is why it works as a story. It reveals the dangers in blindly following tradition by revealing the threat it poses to human life. Hannam and the cast confirmed that this was the message they had in mind in producing the play. If they had chosen to take the play in a different thematic direction, it might have made sense – but that was not the case. All that came from the extra scene was an emotional impact that did not deliver.

In its original form, The Lottery ends in such a way that the audience is left uncomfortable enough that they are forced to examine their own understandings of the performance material. They are allowed to process what the play is trying to say, and to determine that message for themselves, undistracted by emotional fodder – and that makes the superior story.