The Reality of College Preparation at MHS

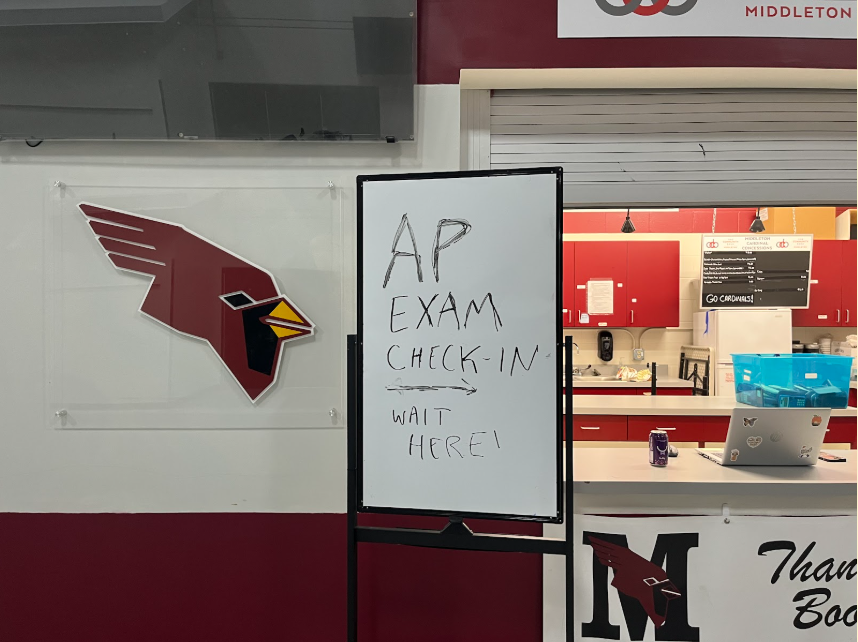

The first week of April marks the final wave of college admissions decisions for high school seniors across the United States. At MHS, the admissions decisions—both positive and negative—of many graduating seniors reveal the effects of a high-pressure high school environment.

April 6, 2020

With the last wave of college admission decisions rolling out across the nation, high school seniors across the nation have until May 1 to finalize their commitment to colleges. The college admissions process in the United States is notoriously stressful, with admissions rates declining annually. It doesn’t end with admissions decisions, either. Seniors must now cope with the stress and anxiety of dealing with rejections, financial aid packages, and the weighty decision of which college to attend.

Middleton, Wisconsin, is a community with many members of high socioeconomic and parents or guardians who are themselves alumni of prestigious schools. As such, MHS is a notoriously competitive high school in the “Big 8” conference region, with graduating seniors going on to attend some of the nation’s most coveted universities every year. The resulting academic culture is often compared to a “pressure cooker” by students and staff, reflecting the stress that hundreds of qualified students feel as they vie for increasingly limited spots at increasingly competitive schools.

On the effect this high-pressure environment has on students, says MHS counselor Marcy Smith, “We don’t know. We’ll never know, because it is what it is.”

Entertaining the idea of a more casual attitude towards post-high school planning may reduce stress on students, but the high-achieving atmosphere at MHS may be the key to pushing students to success. Alternatively, students may allow their values to guide them regardless of the high school environment.

While unable to isolate the exact effect of the environmental conditions at MHS on students, researchers have found competitive high schools to report increased levels of student stress. In a survey conducted by New York University (NYU), researchers found that at competitive schools such as MHS, 49% of students report “a great deal of stress on a daily basis,” and 31% report moderate stress levels. For these students, preparing for college was listed as a key factor in causing stress. The challenge high school counselors are now faced with is balancing student health with high achievements.

“I do think high expectations are really great. We should have high expectations for everybody, but things should be achievable. [High expectations] should never be where they’re affecting someone’s mental health. If you’re not sleeping at night because you’re worried about keeping up with your homework, we’ve got an issue,” says Smith.

High academic expectations are the result of a confluence of factors, including wealth. The 2019 “Varsity Blues” college admissions bribery scandal revealed to families across the United States a fundamental inequality in college admissions. To many, the scandal involving wealthy families who bribed their children’s ways into elite universities unveiled not only criminal corruption but fundamental inequalities in the college admissions process. From legacy preference at elite universities and Dean’s Lists for significant donors to expensive college preparatory courses, the college admissions process in the U.S. exists on a pay-to-play basis for many.

For example, the ACT standardized test recently modified its rules, allowing students to retake subsections of the test without retaking the entire test. In this way, students who can afford multiple test retakes can create a superscored ACT sufficient enough to gain admission to elite universities, while students who can only afford to take the free state-mandated ACT sitting fall behind. Wealthier families are also able to afford ACT tutoring classes, and while MHS offers free ACT preparatory programs for students in need, not all high schools do.

The recent rise in selective college admission has also birthed a new industry in private college counseling, with companies such as CollegeVine and Crimson Education offering to guide students towards elite school admissions at hefty prices. Smith counsels students to be wary of these programs, as they are more than likely not worth the money spent.

“The students that I have worked with that have gotten into the hardest schools to get into have not worked with an outside counselor. They are a really unique individual in a lot of ways, and they don’t need anybody to help make them more unique or to help spin a story of who they are,” says Smith.

Dependence on outside college counselors can even hurt students at times. When it comes down to college applications, school counselors are the ones writing the crucial letters of recommendation and school reports. If a student is absent during the college process, waiting until the day before a deadline to ask for help, MHS counselors do not have the information necessary to write a good letter of recommendation.

“We [MHS counselors] don’t get to have a good enough relationship with [students] because they’re reliant on this outside source. At the end of the day, the outside source isn’t the one that writes the letter of recommendation. I’m the one that writes their letter of rec,” says Smith.

The rise in demand for private counseling service has arrived for a reason. Parents observing increased competition for college admissions worry about whether their child is adequately prepared for the process. Six years ago, MHS did not have four-year planning, but the demand from parents and guardians and worried underclassmen drove the school to implement support for college admissions from a younger age. While underclassmen should focus on finding their footing in high school, not ACT preparation or essay writing, there are reasonable steps younger students can take towards college preparedness, especially for those seeking spots at elite schools.

“Take challenging classes, push yourself where you think you can be pushed, back off where you feel like you have to back off. Get involved in extracurriculars, sports, play, get a job—whatever it may be. Make yourself a well-rounded person, and the rest will come,” says Smith.

Later, as upperclassmen begin to choose schools, prestige should not be the only thing kept in mind. To determine which schools to apply to, Smith recommends students begin with their desired major or course of study and select schools with high support in those areas. However, nearly 80%of U.S. college students change their major at least once with an average major change of three times, according to the National Center for Education Statistics. Therefore, most students should think about other important factors such as fit, location, and finances. Narrowing down which colleges to apply to helps students select which college to attend once admissions decisions are received.

Although Ivy League and similarly elite-status colleges may not be the best fit for most students, high national rankings and prestige draw tens of thousands of applicants to highly selective universities each year. These schools only admit fewer than 10% of applicants, leading students to obsess over how to gain admission, turning to outside college counselors, and expensive college preparation measures. In the end, though, none of these measures guarantee admissions. Even if a counselor were to tell a high school freshman the profile of a student recently admitted to a prestigious university and the freshman were to spend the next four years cultivating an identical profile, the likelihood the student would get into the school would be slim.

“The fact is: we can’t control the other people applying, we can’t control the year, we can’t control you, we can’t control the classes. You can do every single thing to get to this goal . . . and at the end of the day, you might not get in,” says Smith.

Instead of stressing over unpleasant extracurriculars and classes simply because they look good to colleges, students should pursue success within their genuine passions.

The idea that elite colleges make-or-break a student’s life is inaccurate, yet a significant source of grief for students who fail to gain admission.

“People seem to think it has more to do with the college itself than the person, but I would argue the opposite. It has far more to do with the person and less about the college,” says Smith.

Smith likes to remind her students of the true impact of a school with an anecdote she tells in junior seminars: after transferring from Madison College, her cousin’s roommate at UW-Madison graduated top of their medical school class and had her priority pick of any surgical residency in the nation. While Madison College is often looked down upon compared to selective universities, Smith says her cousin’s friend was able to find success, not because of the school she went to, but her intrinsic motivation. Students who attend elite schools often were driven individuals before gaining admission.

“Do I think that if you get into a prestigious university, you’ve got a foot in the door places? Absolutely. Do I think if you don’t go, you’re going to do just fine and do a lot of great things with your life? Absolutely,” says Smith.

Even for the most qualified, highest achieving students, rejections are inevitable—but students should not allow the rejection decision to damage their self-worth.

“To boil that [high school experience] all down to one day and one decision is so sad. Do what you’re doing because you enjoy it, and you want to push yourself, and you have a goal, of course—but at the end of the day, we’re going to be disappointed by a lot of things in life, so we’d better feel happy with the journey along the way. If you’re not happy along the journey . . . it would have been a waste of four years,” says Smith.

When counseling seniors following acceptance decisions, Smith asks seniors to reflect on their experience – and whether, looking back, they would have changed anything.

“What would you change? What could you do differently? No sleep? Not have any friends? Quit your sport? And then you would have sacrificed everything to potentially get the same result,” says Smith.

Most of the time, for her students, the answer is no.

The college admissions cycle is a stressful and intense process, and as long as job markets and educational systems remain competitive, this stress is not likely to go away. However, students can reduce anxiety by remembering their worth is not dependent on college admissions decisions. At the end of the day, successful students can find success wherever they attend, as long as they retain passion, intrinsic motivation, and resilience.