What’s Going On With Disney’s “First” Gay Character?

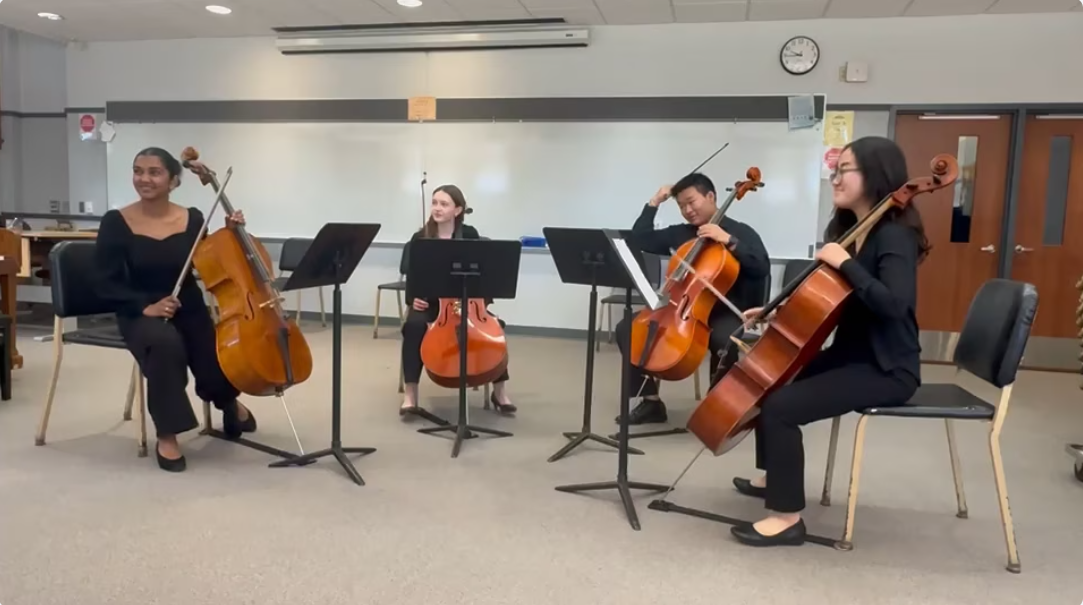

Disney’s Onward featured one of the company’s many “first” LGBTQ+ characters—and this time they may have actually succeeded. Officer Specter, pictured above, is the first Disney character with a line of dialogue explicitly confirming her as a member of the LGBT+ community.

April 24, 2020

On April 3, 2020, Disney’s Onward was made available to Disney+ subscribers, following its March 20 digital release. The latest Pixar movie may be a welcome relief for Disney fans and parents worldwide during quarantine, but five countries have already banned or censored the film, which depicts two young boys bonding over their father’s posthumous magical gift. The reason for this censorship? Onward features Disney’s first openly gay character, a cyclops policewoman voiced by Lena Waithe. Disney calls this a “historic” moment for their company, but this is not the company’s first ‘first gay character,’ as many Disney fans have pointed out.

With the “exclusively gay” LeFou in the 2017 live-action remake of Beauty and the Beast, Zootopia’s possibly-married antelope couple, and Finding Dory’s lesbian couple, Disney is hardly new to dubiously queer characters. These characters are revealed in blink-and-you’ll-miss-it scenes, coded in a way that non-LGBT+ audiences—and certainly not children—are likely to understand. Identifiers such as gay or bisexual are kept far from the silver screen, making it impossible for fans or enemies of LGBT+ portrayals to claim characters’ identities.

Since the Disney renaissance in the 1990s, fans and LGBT+ advocates have criticized the company for “queer coding”—subtextual portrayals of (often negative) traits typically associated with LGBT+ people, and in children’s media, villains. Examples include The Little Mermaid’s Ursula, the raunchy, conniving sea witch modeled after famous drag queen Divine, and more recently, Moana’s flamboyant, campy, and vain, Tamatoa. This “queer coding” dates back to 1953, but it wasn’t until 2017 that Disney publicly confirmed a character to be gay. This “exclusively gay” moment occurred when LeFou, the inane goon to Gaston (whose name translates to ‘the fool’), unwittingly found himself dancing with another man during the final ballroom scene. Despite Disney claiming LeFou as their first gay character, recent press releases have named Finding Dory, Onward, and Jungle Cruise all as movies with Disney’s “first” LGBT+ character, often to backlash both outside of the LGBT+ community and within it.

While anti-LGBT+ sentiments remain present in the United States, much of Disney’s concern surrounding LGBT+ representation concerns foreign markets. China, the world’s second highest-grossing film market, has a history of censorship with LGBT+ characters and films, and it isn’t the only country to do so. Onward, an otherwise unremarkable fantasy family road trip film, was banned in Oman, Kuwait, Qatar, and Saudi Arabia, and censored in Russia due to the single line of LGBT+-suggestive dialogue.

Globally, conversations surrounding LGBT+ people frequently reduce them to their sexuality, increasing resistance to the portrayal of LGBTQ+ characters in children’s media. This simplified view stems from a focus on the sexual aspect of LGBT+ identities, historically done to dehumanize and delegitimize queer people, while in more recent years, it has become a justification for discomfort surrounding portrayals of LGBT+ people, particularly in children’s media. For this reason alone, there is something truly historic about Onward’s LGBT+ representation.

The moment in question occurs when a character named Officer Specter seeks to commiserate with a new stepfather, stating, “It’s not easy being a new parent – my girlfriend’s daughter got me pulling my hair out, OK?” Unlike previous LGBT+ portrayals in Disney films, this moment is both explicit and, for a line delivered by a cyclops, strikingly human. Unlike alleged same-sex couples who might be construed by audiences as friends, roommates, or relatives, or LeFou’s sexuality, which is only explicitly confirmed off-screen, there is no room for denial in Officer Specter’s line. In Finding Dory, Zootopia, and Beauty and the Beast, audiences who are not looking for LGBT+ representation would be hard-pressed to find it and welcome to ignore it, but Onward’s Officer Specter is unquestionably queer. For Disney, this is a major step in the right direction.

Onward’s LGBT+ representation marks progress beyond explicit confirmation. By portraying Officer Specter’s sexuality in the context of family, Disney made their first explicitly gay character both relatable and palatable to a variety of audiences. This moment both depicts and normalizes same-sex parents and portrays the idea that LGBT+ people are defined by more than their sexual attraction. But is this enough?

Many advocates argue that the pace of LGBT+ representation in children’s media is not moving fast enough. After all, in a film empire filled with portrayals of heterosexual romance and teenage self-discovery, LGBT+ children deserve to be represented, too. On the heels of Onward, the 2020 live-action original Jungle Cruise provides hope for a potential expansion of LGBT+ portrayal in children’s films. While Disney has already confirmed the movie will not label the character as gay on-screen, Jungle Cruise may be where Disney can, at last, show us a non-cyclops, significant LGBT+ character, and the reception of this portrayal will be pivotal in determining LGBT+ representation for years to come.