Where Education Fails LGBTQ+ Youth

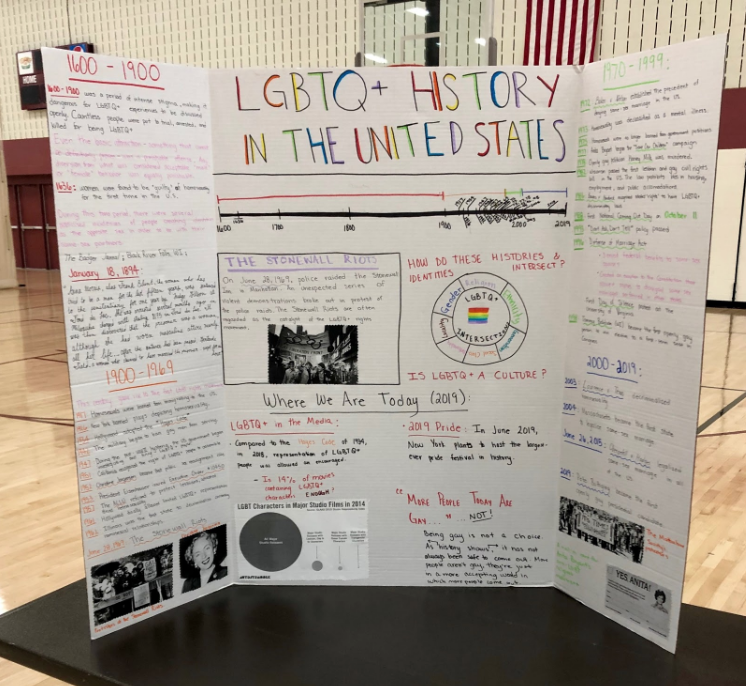

This board, detailing LGBTQ+ history in America, was presented at the 2019 MHS Culture Fair. While some of the events listed on the board, such as the Stonewall Riots, can be found in textbooks used at MHS, LGBTQ+ history is not a major part of most high school curriculums.

May 23, 2020

One year ago, I stood in the field house, presenting my board on LGBTQ+ history for the annual MHS Culture Fair. Person after person walked by my poster board, marveling at the same revelation: how little they knew about LGBTQ+ history.

Most people had a passing familiarity with the Stonewall Riots of 1969, hailed by history as the beginning of the LGBTQ+ rights movement, but few knew the date the Supreme Court of the United States legalized same-sex marriage, or even the year—2015. Unfortunately, this was exactly the reaction I expected walking into the culture fair. From the first moment I realized I was probably-not-straight, I tirelessly pursued any resources I could find to educate myself on LGBTQ+ history and culture. I devoured library books and web pages in search of an answer to my preteen identity crisis, floundering in my lack of education and exposure to LGBTQ+ histories. By the time I stood at my booth at the culture fair years later, the dates and facts presented on my poster were old news, but I had had a reason to learn them. People outside of the LGBTQ+ community did not.

The next semester, I held a game of LGBTQ+ trivia at a meeting of the Sexuality and Gender Equality (SAGE) Club. I expected some questions—marriage statistics and flag symbolism—to be difficult, but the room full of LGBTQ+ students met me with the same lack of familiarity I observed at the culture fair. The people who, in my mind, were “supposed” to have a reason to know their own history, simply did not.

I know this, so should they, I thought, but it was not long before the realization hit me.

I know about LGBTQ+ history because, despite years of social shame and judgment, I was desperate enough for a sense of identity and culture to seek out the answers. I was in a place of self-understanding, without the threat of a homophobic parent finding out about my educational endeavors, and hungry enough to know the history that preceded my experience. I had access to libraries and documentaries and YouTube videos and blog posts, and the freedom to explore labels and identities, but most LGBTQ+ youth do not have those privileges. In the one space where education should be universal, in the classroom, we are neglected.

Representation matters. It matters a lot, and LGBTQ+ youth are deprived of it. Many of us do not have supportive families, much less cultural networks to teach us about our identities and histories. We do not grow up with movies and books representing us beyond negative stereotypes and coded references.

America’s youth of today grew up in a society far more welcoming than any preceding era, but we also grew up on the heels of Don’t Ask Don’t Tell. We are the nieces and nephews and children of parents who survived the AIDS crisis of the 1980s. We grew up without the promise of marriage equality, and we still live in a country that sanctions workplace and medical discrimination. Some of us live in states— including Wisconsin—where murdering LGBTQ+ people has a legitimate legal defense. According to the Human Rights Campaign, 92% of youth report hearing negative messages regarding LGBTQ+ issues, and school is among the top three sources. We walk through the halls of school, showered in slurs and insults into classrooms that ignore our existence.

It is time education does right by its LGBTQ+ youth.

There is no reason not to teach our history. LGBTQ+ history is rich and diverse and beautiful, spanning across continents and time periods. Many of history’s most prolific artists, poets, dancers, musicians, and innovators were members of the LGBTQ+ community, and the influences of our work are reflected everywhere in popular culture. Many of our fondest childhood stories, such as The Beauty and the Beast, are the work of LGBTQ+ artists. LGBTQ+ themes are those of identity, self-discovery, unconditional love, perseverance, empowerment, freedom of expression, and activism; these are themes any child, regardless of identity, will benefit from learning.

Few identities are better suited to discussions of intersectionality than LGBTQ+ identities. Being LGBTQ+ encompasses all genders, socioeconomic statuses, nationalities, ethnicities, cultures, and histories. In an identity belonging to less than 4% of the population, there is something remarkably universal about the LGBTQ+ experience, an experience that cannot be separated from the study of history, art, social sciences, literature, and music, just to name a few.

More importantly, education fosters understanding and acceptance. Every year, the SAGE club collaborates with freshman health classes to present on LGBTQ+ identities, covering the basics of gender and sexual identities, and within these presentations, we make sure to note the harmful nature of slurs through their history.

After one such presentation junior year, I overheard a boy in my Mandarin class use the f-slur. Before I could decide whether it was safe or reasonable to step in myself, his friend asked him not to use the word, educating the offending classmate on the history and harm of the slur. I was overjoyed, of course, to know that my presentation had done something to make our campus culture more accepting, but the exchange made me wonder: if a few juniors could make such an impact through a thirty-minute health presentation, what could an entire lifetime of education do? And why are we being robbed of it?

Before each of these presentations, SAGE gathers volunteers. Already, only a handful of members agree to present, with some of those abstaining, citing the threats members of our club have received after these presentations. As a board, we ask “What can we do to make these presentations more comfortable?”, and when our members ask if we can do anything about the giggles, or the kids arguing against our right to exist, or our peers who sit blank-faced and scroll through their phones even as we talk about something so serious as hate crimes, all we can say is:

“I hope things are better this year,” or, “The teacher should step in.” Never mind all the times they do not.

Students should not have to be the leading educators on their community’s history and experiences, doing it with the fear and shame of belittlement and ignorance. It takes enough courage for us to exist. We should not be forced to bear the burden of educating our peers.

To the educators of today’s youth, I say this:

Education humanizes us. In a world where LGBTQ+ people are demonized and reduced to our sexualities, let us be human.

Approaching our cultural education by forcing us to fend for ourselves only creates isolation and stigma.

Education is a powerful tool. What you choose to withhold from our education sends a powerful message.

By telling kids that they must seek out their history in other spaces, by other means, you tell them that they themselves are “other.” You create an environment wherein an LGBTQ+ student does not feel they can bring their experiences into their education. You reinforce the idea that their identity is a burden and an anomaly and inappropriate for popular discussion, and when you deem our experiences too unimportant to be taught, you deem us too unimportant to be considered.

LGBTQ+ people are not your side note. We are not an acronym to be thrown in for diversity points. We are not one protest in 1969. We are not one line in a textbook that half of your students did not read. You cannot even begin to represent us through the words of that one white cisgender gay man’s poem from 1982 that you might have shown us that one time in eighth grade if the curriculum “allowed for it.”

And your students are children. We should not be responsible for educating ourselves.