What Next Year Might Look Like for Middleton High School and MCPASD

District officials are trying to plan for an uncertain future amid changing local and federal health guidelines.

Education will look different next year.

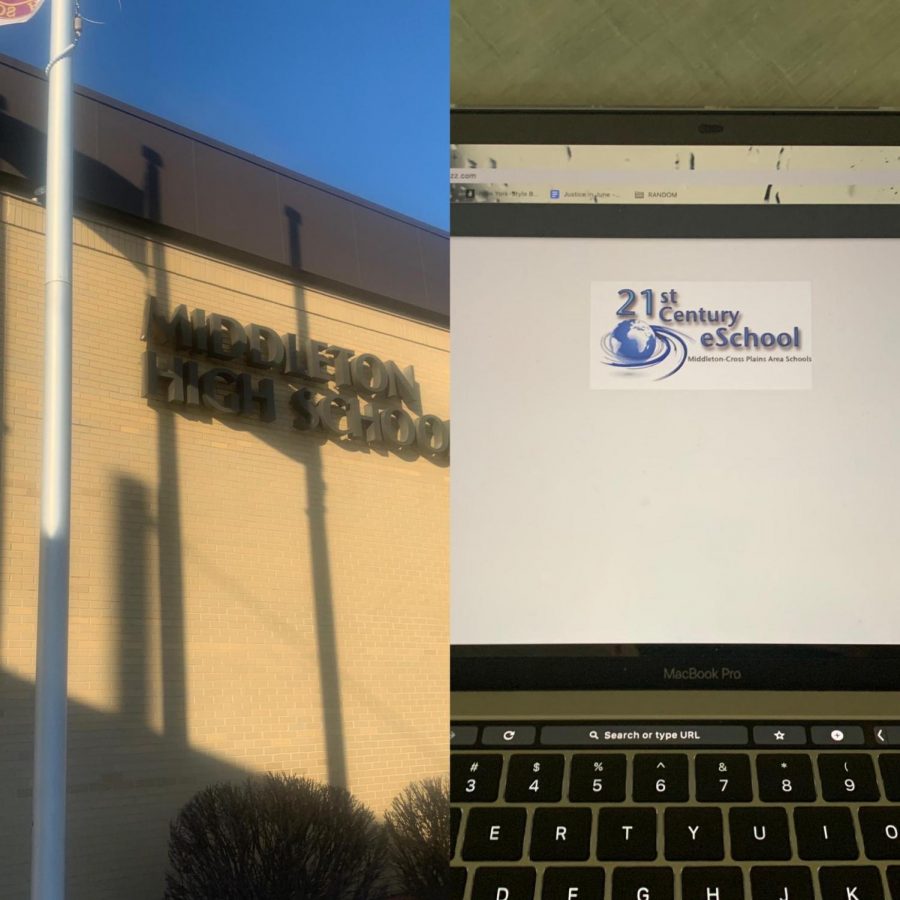

It has already transformed this spring, as Middleton-Cross Plains Area School District transferred all of its schools to virtual learning starting April 1, pursuant to federal and local health guidelines. With health experts predicting that the coronavirus pandemic will continue to curtail mass gatherings for the visible future, K-12 education will continue to transform in the fall of 2020.

The Forward Dane plan, a six-phase approach to reopening set out by Dane County public health officials, will likely dictate much of MCPASD’s capacity to host in-person learning next fall. The plan warns that reopening may not progress linearly: “If metrics are not maintained, we may have to consider returning to a previous phase.”

In response to such uncertainty, MCPASD is preparing three possibilities for next school year: fully in-person learning, fully virtual learning, and a blended model combining in-person and virtual learning.

School officials will spend much of summer flushing out the details of the three plans, since they will be able to step away from the daily planning of this spring’s virtual school. Here is what school officials have been able to share about the three plans so far.

A fully in-person model

A fully in-person learning model would require changes from years past to ensure the health of staff and students.

One possible change might be temperature checks at building entrances, a model many businesses and public agencies are considering nationwide.

Yet temperature checks come fraught with complications. Many health officials have criticized thermal scanning equipment for being unable to consistently and accurately identify those with fevers. Hand-held no-contact thermometers have been relied upon by many, but would not be able to screen thousands of students at one time. Even with large thermal scanners, feeding every student through a temperature check poses issues.

“We can’t get 2,000 kids through one device,” Director of Communications Perry Hibner noted during an interview. “So that also, then, presents questions of: so would we have a couple [of temperature monitoring devices] at the main entrance on Bristol Street? Would we then allow a second . . . [and] allow students to come in the entrance down by the cafeteria? Would we open up the Athletic Entrance and also have a device or two there?”

In total, Hibner estimated anywhere from four to six temperature scanning devices at Middleton High School, two or three at each middle school, and one at the main entrance of each elementary school. “As a District, we would probably need somewhere between 15 and 20 [devices],” Hibner said, which would come with a significant price tag.

Dr. Laura Love, MCPASD Director of Secondary Education, highlighted another logistical complication that would come with in-person learning: bus transportation. With a rapidly expanding student population across the district, buses have held two and sometimes three students to a seat for the past few years. But complying to social distancing regulations would require only one student per seat, perhaps skipping every other row.

“What does that mean, then, for getting kids to school in a timely fashion?” Love wondered. “How many kids can we have in a school setting? What’s the flow of the building? Those are things we really have to think about, whether we’re hybrid [or] face-to-face.”

Beyond logistical considerations, few details have been flushed out regarding an in-person learning model for next fall.

A fully virtual model

The other extreme, fully virtual school, would look different from the virtual system that was implemented this spring.

The virtual school model of the past nine weeks was designed to accommodate the immediate needs and challenges brought on by the coronavirus pandemic. Love explained that the sudden shift to virtual learning was “like rebuilding a system in just a couple weeks. Of course, we have ways of operating, but the ways that we operate in person just sometimes don’t work at all. Sometimes you can just make a shift. And sometimes they work fully. So . . . it was a puzzle.”

This spring, the district faced many challenges that could recur if virtual learning continued in the fall. Some challenges were technical, such as ensuring that every student had a device and WiFi. Others were personnel-based: teachers, as well as students, were suddenly thrust into upended home lives and had to balance home responsibilities with school responsibilities.

Perhaps the largest challenges were decision-based. In March, the district had to decide which platform to use for virtual schooling. At the elementary level, the district used Seesaw and Google Classroom to fit the needs of younger students. For secondary education, Google Classroom and Buzz were the top contenders, with the district ultimately choosing Buzz.

District officials, including Love, acknowledged that Google Classroom was familiar to many students and teachers. “It [seemed] to be the most seamless transition from what was in-person to virtual,” Love said. “And yet there were some challenges with selecting Google Classroom versus Buzz.”

Buzz allowed school counselors to efficiently check student progress by referring to one page of diagnostics, instead of having to check student progress class by class on Google Classroom. “[Buzz] is a whole learning management system package that even gives parents and families access to information that we wouldn’t have had directly in Google Classroom,” Love said.

Buzz also had pre-planned online curriculum for many classes that teachers could “drag and drop” into their timelines. This helped teachers make the shift to virtual learning, but also presented an issue to students.

“A theme that I heard is kids were bored,” said MHS Principal Peg Shoemaker. Shoemaker has recently sought input about virtual learning from around 30 MHS students.

The student boredom raises some questions for continued virtual learning. “How do we train our teachers to be able to really teach in a virtual environment? Because we didn’t have any time to do that,” Shoemaker said, noting that many teachers had to transition online without learning strategies and engagement tools tailored to virtual learning. She wants to help teachers plan engaging virtual curriculum if online school were to continue in the fall.

Love commented on the added difficulty of “Zoom exhaustion,” with multiple screens making it difficult to connect to others on a personal level. Some people have glasses, or some people get tired sitting in front of the computer all day. “And you have another meeting that’s an important meeting at the end of the day, but you’re already cross-eyed and your neck hurts,” Love said.

Were virtual learning to continue in the fall, engaging curriculum might be paired with strategies to combat “Zoom exhaustion” to keep students interested in school.

Another priority for Shoemaker is fostering community within a virtually-run MHS. That pertains to student-teacher relationships as well as connections among the student body. This year, Shoemaker noted, the school had around three-fourths of the year to establish community.

“How are we going to do that when a teacher and a group of students don’t know each other?” Shoemaker wondered. “Establishing that classroom community is really, really important. . . . So that will be something that we’re working on this summer. How do we give teachers the tools they need to help establish that relationship with kids?”

Some students have informed Shoemaker that they need to see their teacher’s face to build that relationship. “They really would like for a teacher to be live for the class, and then record that so that they’re actually seeing the teacher,” Shoemaker said. “Kids have talked about, it’s not motivating to just get an assignment and not have a teacher’s face connected to it.” Students have also expressed a desire for Shoemaker to follow the A/B block schedule, even when in a virtual learning system, to help them focus on essential learning.

Building community between students is imperative to Shoemaker. “When you think about the essence of high school—for most kids, [it] has everything to do with social life. . . . A lot of it is built around human connection. And so when that is missing, some kids just drop off,” Shoemaker said, connecting it to one of her top priorities, student mental health.

Relationships between teachers and district personnel are also essential to virtual learning, noted Love. Her priorities for improving virtual learning include community building and connections, collaboration between teachers, and ensuring that teachers agree on essential learning standards so they can multiply their work.

Many staff, as well as students, have faced difficulty in the transition to virtual learning, attempting to adapt their role to a new setting. Paraprofessionals, bilingual resource teachers, coaches, administrators, and more all serve students in various ways that are difficult to translate to virtual learning.

One such group that had to translate their roles to virtual learning is the district’s ESL and bilingual resource teachers. The ESL team works to meet the needs of around 440 English learners in the district, half of whom speak Spanish and the other half of whom encompass about 40 different languages. Mandi Sersch-Morstad, MCPASD Director of Bilingual Services, explained how ESL and bilingual resource teachers adapted their roles to virtual learning this spring.

First, the district established routes of communication for families. District officials worked hard to ensure that all large-scale communications went out in Spanish. School-based bilingual team members assisted with individual family communication. Educators used online language resources to engage with families in languages other than Spanish.

The ESL and bilingual resource team then focused on working with teachers and students. In a normal school setting, ESL and bilingual resource teachers collaborate frequently with teachers to ensure that the academic content is accessible to students who are learning English. That collaboration continued into virtual learning, aided by flexible schedules.

Virtual learning also fostered strong connections between teachers and families. “I think our ESL and bilingual resource teachers have always had pretty deep connections with their students’ families, just given the nature of their role,” Sersch-Morstad said. “So to see even more teachers and educators make connections with families has been awesome, and I hope that’s something that we see continue.”

Across the district, teachers have tried to meet all students’ needs by paring their content down to essential learning. The focus on essential learning has helped many students to be able to focus in the trying environment of the pandemic, including English learners.

District officials are hoping to apply the lessons gained in this spring’s virtual learning to plans for the fall. “As we move into the fall, what do we take from what we’re doing now that we see that’s working really, really well?” Sersch-Morstad asked. She cited the flexible schedule as an example of a new tactic that has benefitted some students, allowing them to access school during nontraditional hours. “Some are working with siblings or doing other things for their family and might not be able to tap into their classes during the typical school hours, so having that flexibility has been great.”

To gain input about what has and hasn’t worked this spring, the district recently surveyed families about virtual learning. The survey asked whether families thought the amount of time spent on school was appropriate for their children.

At the elementary level, two-thirds of families thought the amount of instruction that was being provided was appropriate, according to Perry Hibner. “That number decreased, though, when we talked to middle and high school families,” Hibner said. Around 55% of families at the middle school level and around 50% of families at the high school level thought the amount of instruction that was being provided was appropriate.

“Now, is that that [sic] families felt that we were providing too little?” Hibner asked. The district has not examined the data enough to know if families were asking for more or less time spent on school. “We need to do more digging on that,” Hibner said. “. . . Because you don’t want to make an assumption.”

Some families have faced challenges in virtual learning that have led to their students spending more time on the computer than their lessons dictated. “Maybe they’re an English language learner, and it’s taking them a long time to understand the directions,” Hibner said. “Maybe they only have one device and they’re sharing among multiple children. And so, while these kids are only getting three hours, it feels like the family themselves is having to do it all day long, and they’re frustrated by that. So those are some things we need to find out more.”

The district plans to release a second survey at the end of June to gather more information from families about virtual learning.

One of the district’s struggles moving forward will be accommodating students who are struggling with virtual learning alongside students who are seeking more from virtual learning. “Even if it’s partial online or if it’s fully online in the fall, I think that’s going to be the struggle—not just for Middleton High School, but for all schools—all levels, and all districts—is trying to make sure that we provide the appropriate experience for students,” said Hibner.

Sersch-Morstad emphasized the importance of acknowledging student differences. “We do need to keep in mind that while we have had some kids and families who have had more struggles with the online environment, particularly due to—technology, for some, has been really challenging—we’ve also had some who have been really thriving in the environment,” Sersch-Morstad said. “So I think [we should be] really thoughtful about not lumping everybody together in one group.”

Many of the details about how virtual learning might look in the fall also apply to a blended model.

A blended model

A blended model for next fall—a combination of in-person and virtual learning—raises the most questions about how it might function.

“I would say fully virtual and fully in school are probably the most known things,” Love said. “We’ve already experienced both of those in one year. What a blended or hybrid model might look like is a hundred possible different ways of operating.”

The blended model, Hibner shared, “is what a lot of us are thinking will probably happen.”

Hibner proposed an example of a blended model at the high school: some students come on Mondays and Tuesdays, other students come on Wednesdays and Thursdays. Fridays might alternate between the two groups every other week, or be a day of online learning for everyone. “When you’re not in school, you would be doing online learning,” Hibner said.

The blended model would face difficulty reacting to changing recommendations from health officials.

Hibner cited an example of size restrictions on indoor gatherings: “Are [health officials] going to say that a school the size of Middleton High School can only have 250 students in at a time?” Given the enrollment of MHS, a 250-student limit would mean that a student would come into school every eight or nine days. “Well, that doesn’t make a lot of sense,” Hibner said. “Why would you have one day in school and eight days online? You would probably just stay with all online, in the short term. We don’t know what the county and . . . the state agencies [are] going to recommend.”

Still, if schools get shut down again in the fall, whether MCPASD is in a blended model or fully in-person model, Hibner said, “I think we’ll be better prepared for that than we were when this happened the first time.”

Love added, “[The] hybrid model is the one that we need to work on the most, and that’s where we’re probably going to put the most of our energy.” Even if the district is fully virtual, “we’re going to have to reconceptualize,” Love said. “We’ve got to do a better job. Now that we’ve learned from these experiences, what’s most important, what’s actually working, what’s not working.”

Grading

Whichever system is used in the fall, MCPASD will have to decide whether to continue with this spring’s Pass/No Pass grading system. District officials have only recently begun conversations about grading moving forward.

Grading at the elementary and middle school levels poses less difficulty than at the high school level. At the elementary level, “As long as you’re learning, as long as you’re showing you’re getting the core competencies, you’re going to move from first to second grade, second to third, so on and so forth,” Hibner said. “So getting a letter grade probably is not as big a deal because there’s not a GPA component that makes a difference there. Same thing, even, at the middle school level. It might be nice to get grades, but in the big scheme of things, you’re all starting over again once you get to high school.”

Grading at the high school level raises more complicated questions. Many students at MHS want to continue on to college, and in that regard, grades and transcripts matter. Colleges have expressed that they are going to be understanding about what happened this year—but will they continue to be understanding about Pass/No Pass grading systems in future years? “That’s not what colleges want,” Hibner said, noting that they want to see where kids fall on a spectrum.

Next year’s grading system “probably will depend on how much redesign can happen by teachers,” Love said. In the sudden shift to virtual learning this spring, teachers were unable to assess students in the same way as before. Pass/No Pass aided teachers new to virtual learning as much as it aided students who may have struggled to access virtual learning.

The language of Pass/No Pass depicts the goal of that grading system. “We didn’t want to say Pass/Fail, because a Fail means something quite different from a No Pass,” Love said. She highlighted that only some students had full access to teaching and learning from the beginning. “Because we had to turn on a dime, we couldn’t guarantee that this wouldn’t disadvantage kids from the beginning.”

Love likened Pass/No Pass to a Pass/Withdraw system at a university: “If I were able to withdraw [from a class] in a certain timeframe, it doesn’t count against me as a student. It’s simply an acknowledgement that there was just no way for me to achieve a passing grade. And yet, I didn’t fail the course because I didn’t really have access to the course fully.”

Love considers grading “one small piece, really, of all the planning that needs to happen for us to make a good determination that doesn’t put students in a precarious position.” Therefore, one option under consideration for the fall is a combination of Pass/No Pass grading and letter grades. If a student had barriers that prevented them from achieving in a manner translatable to a letter grade scale, they could choose Pass/No Pass grading for some of their classes. “I know some schools and districts did that this spring,” Love said. “That could be where we land at the high school level in the fall.”

Hibner guesses that the district will release concrete information about the upcoming school year sometime in August. “One, because we’re hoping we’ll get more direction from the county and the state; but two, we want to make sure whatever they announce, that we’ve got a plan in place to make that work,” Hibner said.

An innovative curriculum

The virtual learning shakeup brought on by the coronavirus pandemic intersects with ongoing conversations in MCPASD regarding 9-12 educational redesign.

The 9-12 redesign efforts were launched by the district as part of planning for the new high school building. The new building, scheduled for construction over the next few years, will replace most of the current MHS building and incorporate Clark Street Community School into its structure.

Love, in her position as Director of Secondary Education, coordinated with the Director of Elementary Education during 9-12 redesign plans. As they discussed the district’s portrait of a graduate—the six to eight characteristics the district wants to ensure every student masters—they realized that their ambitions extend beyond 9-12. “It starts much earlier than that, and we have to make sure . . . that we’re giving kids early and often opportunities for revisiting maybe more and more complex tasks around that particular characteristic,” Love said.

Shoemaker, who worked at another high school that recently finished a building remodel before coming to Middleton, is excited to pursue innovative educational models at MHS. “I think many would agree that we have a nationwide issue of remaking a traditional high school,” Shoemaker said. High schools, she observed, have not changed much since they were first introduced. “Your kids are still in rows, your teacher is standing at the front imparting the knowledge, and . . . that does not engage kids. Kids have so much more potential to . . . act on their life through choice and having voice. . . . I think we can do high school a lot better.”

To that end, Shoemaker is looking for ways to give students more agency in their schooling, both via classroom-specific strategies and school-wide intentions.

One of the innovations under consideration for MHS is topic-focused strands, loosely inspired by a career academy model. Strands would allow students to personalize their education based on their passions, exploring concepts such as social justice, hip hop, or global analytics across every subject requirement.

What virtual learning has shown this spring is that students do not need to be present in a building to engage in personalized learning. “So how can we build upon that as we’re looking for innovations?” Shoemaker wondered.

Technology has broken down the barriers of the rigid, traditional school schedule, which operates differently than the working world. “When I think about businesses that are really built upon innovation, your workload . . . [is] a meld,” Shoemaker said. “. . . How do we replicate the way work really is with how school is operating?”

An unanticipated effect of virtual learning Shoemaker observed this spring is that “it got teachers to a place that they could start to envision: how could we be more creative and allow much more personalization within our students?”

MHS has already started to experiment with innovative curriculum, such as with the Hip Hop Evolution class that premiered this year. The class, offered as a combination of Fine Arts and Social Studies curriculum, is the precursor to a Hip Hop Music Production Academy Shoemaker eventually hopes to establish as one of the “strands” available at MHS.

In this strand, students would work through a course load underscoring the theme of hip hop throughout all classes: physical education, English, social studies, etc. One specialized class could be a business marketing class that connects students to individuals in the hip hop industry, so that students have the potential to further their passion and careers through that route.

The Hip Hop Music Academy will slowly be introduced into the MHS curriculum, with a second Hip Hop Evolution class debuting next year, followed by another related class the year after. “It’s opening the floodgates to what school can look like,” Shoemaker said. “. . . I mean, this is going to be cutting-edge, what we’re going to do.”

Paired with new lessons from this spring about the potential of virtual learning, curriculum innovation will continue in MCPASD. District officials across the board are excited about the possibilities moving forward.

Love thinks MCPASD has a great opportunity to reconceptualize what matters most for students’ futures, and how that pairs with essential skills, knowledge, and understanding. A question driving her work is: how do we make school relevant to students—culturally relevant, relevant to their daily lives, and relevant to what they want to do in the future? “I think that’s the opportunity for us to redesign or reconceptualize the system, and give students a lot more voice and choice,” Love said.

Sersch-Morstad reflected on the spirit that drove MCPASD staff to come together and make online school work during this spring. She hopes to reflect on and continue that energy in the fall. “We have so many opportunities to reconceptualize things. . . . It’s an exciting time,” Sersch-Morstad said. “It’s nerve-wracking, because we have this event that happened that totally shook up our system. But I tend to be a glass-half-full kind of person, and I think that it’s an opportunity at the same time to really rethink education and make it even better.”