What Is It Like To Be an AP Reader?

AP readers gather at several sites across the country in the first few weeks of June to grade AP exams from students across the country and globe. This year’s AP exams commence on May 1, and grading lasts from June 1 to June 17.

April 28, 2023

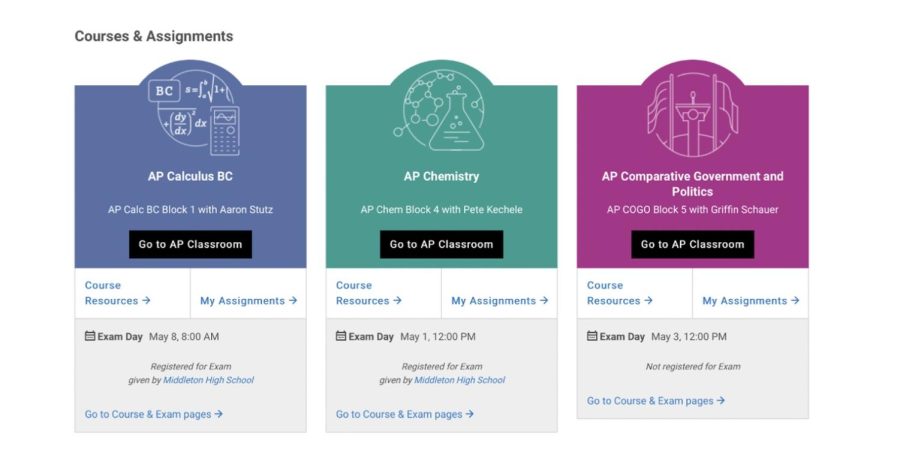

The weeks of May 1 and May 8, high school students across the nation and globe will take their Advanced Placement (AP) Exams for a chance to earn college credit. The exams culminate year-long — and in few cases semester-long — high school courses that are designed to mimic college rigor. Students who score high enough on the exam can often get college credit or skip introductory courses upon entering college.

Despite the exams’ benefits, April finds AP students stressing over the content they need to review and the units they have yet to cover in class as May unyieldingly approaches.

AP exam grades can feel like a strategic shot in the dark, fueled by perplexing AP Classroom mini quizzes and ensuing anxiety-driven albert.io score calculator searches mid study session. But behind the curtain of the College Board’s mysterious grading process are thousands of teachers, the AP Wizards of Oz, who grade with a surprising level of uniformity.

Applying to Be an AP Reader

In 2022, over 2.6 million students took the AP exams, and the College Board hired over 20,000 AP readers to score these students’ 4.76 million total exams. AP tests consist of multiple-choice and free-response questions (FRQs), which hold different weighting depending on the exam. AP readers only score the students’ FRQs.

High school teachers and college faculty can apply to score AP exams in their subject. AP readers must meet a minimum threshold of background in teaching their subject, which for high school teachers means three years of teaching the AP course and the submission of a course syllabus.

College faculty must have taught at least one semester of a course similar to the AP curriculum within three years of grading the exams. They must also be an active member of the university at the time of grading. In some cases, graduate students grade AP exams, and they must meet the same requirements as faculty.

Most AP readers live and teach in the United States. The College Board requires all grading, onsite or online, to take place within the 50 states and Puerto Rico.

Onsite Grading

From February to May each year, the College Board invites qualified applicants to grade in person or online. Middleton High School has several AP readers of its own who grade FRQs by students across the country every June.

AP Human Geography teacher Jeffrey Hayward graded AP FRQs for the first time in 2019 after hearing about AP reading’s benefits as a professional development experience.

“It’s really collegial,” Hayward said. “You get to talk about how you teach the class, best practices, … good strategies to teach how to answer the FRQ. It’s a lot of discussion with your peers from all over the country.”

Although Hayward will not attend the AP reading this year, AP English Literature and Composition teacher Kris Cody will be grading online for the third consecutive year, and AP Psychology teacher Brian Byrne, who began grading in 2017, will grade in person.

“The day after school’s out I fly out to Tampa to grade AP Psychology AP free response questions,” Byrne said.

Each section of AP reading occupies a full room at a convention center, filling halls with hundreds of readers who grade for eight hours a day, seven days straight, reading responses to the same question often over a thousand times in total. During this time, they confer with table partners when they are unsure how to score a response and get a chance to discuss pedagogy with teachers and college professors.

“There’ll be times when you don’t talk to anybody for a while, you’re just kind of in a zone. But then you’re like, ‘Okay, does this answer actually fit this criteria?’ And that’s when you have those conversations happen and you talk to either… your elbow partner, or you can go up to the table lead and ask them,” Hayward said.

A big draw to the AP exams, in addition to professional development, is the camaraderie.

Over the course of the week, each reader grades over 1000 student responses. Byrne reads about 200 a day, or 1400 in total, but some AP Psychology graders read up to 2000. “They’re called aliens,” Byrne said.

Since the philosophy of AP reading is to look for reasons to give students credit, not take it away, readers of most subjects are required to read every response in full. That includes throw-away responses.

“I had a kid write all the lyrics, chorus to ‘Ice Ice Baby,’” said Byrne. “We have to read every word. Even with the ‘Ice Ice Baby’ one I had to go through it to make sure they didn’t get any points, because we’re always looking for points. We’re not trying to take away points.”

While the AP readers do not recommend writing a silly FRQ response, Byrne, Cody and Hayward agreed that those responses do provide a short reprieve from the monotony of grading. For the in-person readers, those responses are another thing to share with the person sitting next to them.

Offsite Grading

In 2020, at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, the College Board rapidly shifted its grading system online to allow for remote grading, something that had been in the works for several years, according to Hayward. Since then, the College Board has allowed AP readers to grade exams at home rather than onsite. Cody seized the opportunity to try grading in 2021, since her schedule does not allow her to travel for AP reading.

“The College Board puts a lot of their training materials behind paywalls, or access walls, and I wanted to know how they score, because even when I read some of their scoring notes and everything else, they aren’t really specific,” Cody said. “I wanted to know what I was doing as a teacher, and the only way to really do that was to score.”

Cody’s experience differs from that of in-person readers, but many of the processes are the same. On the first day, she had a brief meeting with her table reader and the other people at her “table,” where the table reader oriented readers to the grading interface, the question they would grade and the rubric.

Once that twenty-minute orientation is over, online readers go into training mode before they grade for real. They score sample training essays on their own and receive feedback on how accurate they were to the rubric.

Although Cody misses out on the face-to-face interaction by grading online, she still feels the professional development is valuable and has made her a more effective AP teacher.

“I feel more confident that I am meeting your needs. I feel more confident I am putting my priorities on what I should prioritize,” she said.

Accuracy

By the end of the seventh day, after 56 hours of grading, AP readers are exhausted.

“If you start on a Sunday, by Wednesday or Thursday, you kind of hit a wall. And you need to take more breaks,” Hayward said. “You’re not… stuck to your chair, you can stand up and take a walk if you need it. You really try to score it the same way [on the] first day as you do the last day.”

Fortunately, at that point of fatigue, most readers are very comfortable with their question. The College Board starts the week with training, and it eases up its eagle eye on the readers as the week progresses.

On the first day of grading, AP readers “calibrate” to the rubric. In person, they read student responses along with the rest of their table, and the table leader leads them through discussion on how to score each one according to College Board’s highly specific rubric. By day two, for most subjects readers grade on their own with checks on accuracy by the table leader and computer system.

Since 2020, the College Board has taken more measures to ensure the accuracy of each grader. Now that even in-person reading has become digital, the College Board is able to easily track readers’ accuracy and report it back to them in real time. The system cycles pre-graded tests through each reader’s queue of student responses to see if the readers are grading according to the rubric and ending up with the correct scores.

“You have a meter that tells you how accurate you’re being. So that’s kind of intense,” Hayward said. “They say you need to be one with the rubric.”

Online and in person, the table readers also check in on how readers are scoring. AP readers are split up into a sort of College Board hierarchy, with about ten readers at each table working under a table leader, and with table leaders reporting to a question leader at the head table who oversees all the grading of one question in the free response section.

Whenever problems arise with how to score a certain response, it gets passed up the ladder, first to the table leader and then, if needed, on to the question leader. Accuracy is the priority. The AP readers at MHS all felt confident that their colleagues graded fairly despite fatigue and time pressure.

“The people that can’t hack it, they get asked to leave,” Byrne said. He has seen it happen, but not very often.

Advice for AP Students

Given all the time the AP readers at MHS pour into their AP classes, from the first unit in September to the grading marathon in June, they had some valuable pieces of advice for students taking the exams.

In the weeks before the exam, students should expose themselves to as many ideas as possible by peer reviewing and reading student samples. Since starting peer review in his own classes, Byrne has seen his students’ scores on the AP exam improve.

Students should be as specific as possible and provide examples in their FRQ responses, as examples will often earn students a point. If students do not know an example or the answer, Hayward recommends thinking along the course theme. For AP Human Geography, that means thinking geographically.

Finally, in the last dire minutes when their response seems glaring with mistakes, students should know that the scorers are on their side.

“It’s never about deficiencies, it’s about what’s in place,” Cody said. AP readers are looking to give points. For Cody, who scores essays for AP English Literature and Composition, she is searching each exam for a line of reasoning and evidence to support it.

“We are looking to see what’s there, and you can misstep, you can spell incorrectly, you can have information or interpretations that [are confusing] as long as you arrive at that point. And our job is to see that arrival,” she said.

Going into next year, Cody stressed the importance of working toward the exam all year, not just in the last month.

“Students should be alert to the type of test that they are taking, because some of them you can study for and kind of cram that information in your head — AP Lit is not that test,” Cody said. “You have to have been doing the hard work both semesters to be ready for the test. So watch your study skills. Fully engage in the true learning, and always, in any learning environment, scope out what the quote ‘game’ is in order to know how to be successful in the final round.”

2023 Grading Timeline

This year’s AP exam scoring kicks off on June 1 with United States History and Spanish Literature and Culture, and it ends on June 17 with Biology, Calculus, Music Theory and Statistics. In those two and a half weeks, exams from 32 courses will be graded, each over the course of just seven days.

Exam scores will be released to students in mid July.