Book spoilers ahead

Trigger Warning: mentions of gun violence

In a time when the idea of a school shooting has become too familiar, it is important to raise awareness of it in all forms of media. But at what point does bringing such a real issue into fiction do more harm than good?

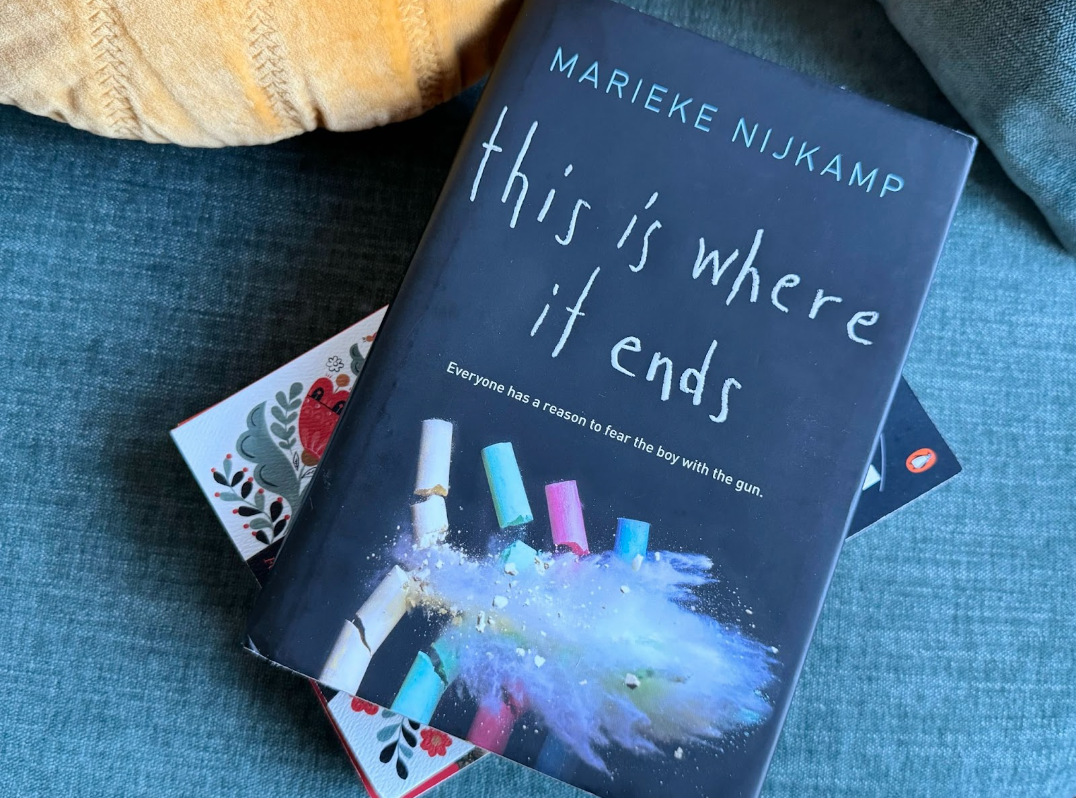

“This Is Where It Ends,” published in 2016, is a minute-by-minute replay of when fictional teenager Tyler Browne brought a gun to his Alabama high school and killed 39 students and faculty. The story is told from the perspectives of four students: Claire, Tyler’s ex-girlfriend; Autumn, his sister; Sylvia, Autumn’s girlfriend; and Tomás, Sylvia’s twin brother. Although this is a work of fiction, it reflects what has happened to too many schools across the U.S.

The book opens with students moving to exit an assembly, only to realize they are locked in the auditorium. As the commotion begins, Tyler steps in and everyone becomes silent. He announces: “Principal Trenton, I have a question,” aims his gun and fires. From then on, Tyler’s witty lines and speeches veer further and further away from any sense of realism.

Whether the goal was to make Tyler look more “crazy” or to make his plan appear rehearsed, portraying his character in such a cartoonish way invalidated the reality of similar situations.

After another set of taunting remarks, Autumn describes her brother as having always had “a flair for the dramatic.” This becomes even clearer when Tyler forces Autumn, who is auditioning for Juilliard, to dance for him onstage.

Moments such as this were when Nijkamp toed the line of realistic fiction—she seemed to write with an intense and believable tone, but some parts were too far-fetched. Amidst all the attempted suspense, the tone sometimes seemed to romanticize the situation, making scenes intended to be wholesome suddenly jarring and confusing.

A successful action novel can push the boundaries of what would happen in real life. In the case of “This Is Where It Ends,” the author’s attempt to immerse the reader combined with the implausible situations and tropes made it feel like a book that doesn’t know what it wants to be.

Another aspect that felt too fictional was that Nijkamp depicted the high school characters as exaggerated archetypes. Every time something horrible happened, it happened to the cheerleader, the freshman or the mathlete. This could work as an intentional choice, but it felt wrong when applied to such a serious topic; it seemed to counteract the book’s message. Each character was portrayed through a lens of black and white—the four protagonists were the heroes, their flaws forgiven for the greater good, and Tyler was the villain, his motives and emotions barely extending beyond those 54 minutes.

This dynamic reaches its most dramatic point near the end of the book when Tomás saves Sylvia by confronting Tyler alone, an action that feels more ignorant than heroic. He gives Sylvia a last-words speech in which he looks back on his fondest pranks, still maintaining his troublemaker stereotype despite having matured significantly during the traumatic situation. He then approaches Tyler in the abandoned school building, beginning the climax of the story with more artificial dialogue:

“‘You know, sweaty chic doesn’t suit you,’ I muse.

Tyler falters, though only for a moment. ‘I should have known. Come to protect your sister? What are you going to do—hit me again?’”

Tyler’s persistent “coolness” and edgy personality reinforce the idea that he is an unavoidable force of evil, providing a poor representation of a likely complex situation that involves mental illness.

Perhaps the most poorly executed part of “This Is Where It Ends” was that it mentioned nothing problematic about school shootings, despite describing that the students knew it could always happen to them. School shootings should not be normalized as something inevitable, like a natural disaster; they are a problem that must be solved, and treating them as scary yet unfixable will not help. Between the years of 2009 and 2018, the United States was the country with the most school shootings at 288 incidences. Mexico, the country with the second-highest number of school shootings, had eight.

With data this shocking, it’s undeniable that when this subject is discussed, it cannot be taken as fictional or unavoidable. Nijkamp is Dutch and has never attended an American high school. Zero records exist of school shootings in the Netherlands. This is interesting to note because readers outside the U.S. may find this book much more enjoyable— it is not about a real threat they have to face every day that they go to school.

Gun violence is the leading cause of death for minors in the U.S. Because she did not address this, Nijkamp took advantage of a serious concern to write an exciting thriller. The book was specifically marketed to American young adults, for whom the premise may even feel dangerous. No well-known school shootings have involved trapping an entire student body in an auditorium. There is no way to know if expressing this concept in the media could plant an idea in the wrong person’s mind, something Nijkamp should have been much more careful with.

She tiptoes around any sensitive topics, avoiding anything beyond vague hints at Tyler’s mental health or his harassment of Sylvia. The characters’ flashbacks allude to Tyler facing his father’s abuse, but do not go into any detail, expecting the reader to simply “know how it is.”

As if the book’s content wasn’t problematic enough, some editions feature a themed playlist at the end, including songs such as “Anthem of Our Dying Day” by Story of the Year and “Royals” by Lorde. The idea of romanticizing something that has killed and traumatized countless people as far as creating a playlist feels unbelievable. How can it be appropriate to tell a story inspired by true events where innocent people were killed and conclude it with a list of songs for readers to match its “aesthetic”?

In the U.S., over 22 million children and teens live with a gun in their home. Autumn narrates, “Where did he even get the gun? One of the trade shows Dad used to attend?” This was not mentioned again in the book. The author completely skips what is one of the most important factors of ending gun violence in schools, showing a lack of understanding for the issue that should have been backed by more research and hearing real-life accounts.

60 Minutes Australia conducted a frightening interview with convicted Alaska school shooter Evan Ramsey, who spoke on the impact of having access to a gun. “If I didn’t have access to a gun, I wouldn’t be doing this prison sentence,” Ramsey said. “If children didn’t have such easy access to firearms, then yes, these types of crimes would not happen.”

Gun violence is a horrible crime, and those who hurt innocent people should not be forgiven. No difficulties someone has faced can justify taking the lives of others. Furthermore, the harm can be compounded when popular media like “This Is Where It Ends” tries to tell a story without acknowledging information beyond what is on the surface. It is essential to recognize the impact that uninformed writing can have and consider the full context of a story—more accurate information means less risk of repeating what will someday, hopefully be history.