As March ends, AP tests seem to be right around the corner. After that, the dreaded finals week emerges in June. Now is the perfect opportunity to discover some new ways to learn that might just make your review days a little easier.

1. Active Recall

Simply rereading textbook sections or notes you have taken in class is often both time-consuming and boring. Rereading is also not effective for memory retention. Instead, try using active retrieval techniques, such as flashcards or practice questions. Surprisingly, you learn best not when you are intaking material, but when you are pulling it from your knowledge. By going through retrieval practice, you are also better able to assess what topics you are more familiar with and what topics need extra refreshers.

Use flashcards by writing down terms on one side, and definitions on the other. This is easily done on websites such as Quizlet and Knowt, but can also be useful when written by hand. Try looking at the term and saying what you believe the definition to be out loud before flipping the card over. Using flashcards well is a convenient way to review key vocabulary, concepts or events.

Doing practice questions is another great way to review, especially if you have already gone through your material and know it reasonably well. Not only do practice questions cover a wide range of subjects, but they also help you become more familiar with the format of a course’s test questions, whether it’s multiple choice or short answer. Even if you do not perform well on a practice quiz, you are setting yourself up for success in the actual exam simply by practicing.

2. The Leitner System

If you do decide to use flashcards, it is worth thinking about how you can organize your flashcard review to be more effective. Going through each flashcard may work well for the first time you are looking at a set, but it gets redundant over time.

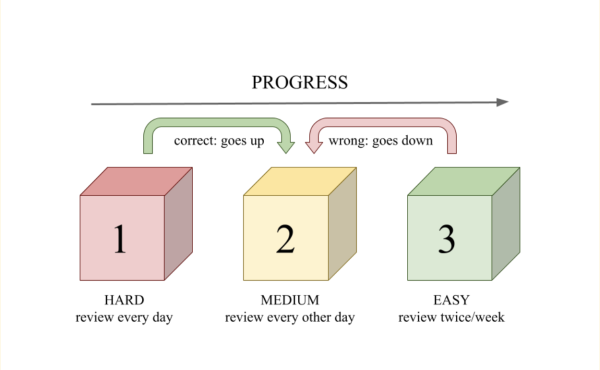

Instead, try the Leitner system! Created by Sebastian Leitner, a German science journalist, the system relies on dividing flashcard review frequency depending on familiarity. To do this, you can use 3-5 physical or digital “boxes” to store flashcards. Each box should be reviewed at a different frequency. For example: Box 1 is reviewed every day, Box 2 every other day and Box 3 twice a week.

All your flashcards should first be placed in the first box. When you review them, move the flashcard up one box if you get the answer correct, or down one box if you get it wrong. In the case of Box 1, you would move the card to Box 2 if you got it correct, and keep it in Box 1 if you got it wrong. Similarly, if you get a card in Box 2 wrong, move it back down to Box 1; if you get it correct, move it to Box 3.

The goal is to have all your flashcards in the highest box by the time you need to take your test, but it is a good idea to keep adding more flashcards as you learn new material. This ensures you are always periodically reviewing all the information and that you’re focused on the concepts that need to be reviewed the most.

3. Feynman Technique

Have you ever explained a topic to a friend or classmate and found yourself understanding it clearer afterwards? Or, while you were explaining, realized that you did not actually understand it at all? Both of these scenarios explain the essence of the Feynman Technique, which was invented by Nobel Prize-winning physicist Richard Feynman.

The technique asks you to explain the material, whether it is an event or concept, as if you were talking to a sixth-grader. To do this, write down everything you know on a blank piece of paper. You can also speak aloud as if you were guiding the sixth-grader through your writing. You will likely find that there are some concepts or vocabulary that you do not actually fully comprehend, and can not explain simply.

The next step is to go back through your explanation and research the areas you struggled with, which can be as simple as a Google search. If you have time, try to repeat the explanation until it comes out clear and concise. Try to simplify what you have written, and you will end up with a nice set of notes as well.

Finally, you might want to try to run your explanation past someone you know. If you know a sixth-grader, that’s perfect! If not, you can explain it to a sibling, a parent or a friend. This last step makes sure the knowledge is firmly established in your mind.

4. Mind Mapping

You have probably made a mind map at some point in your life, or at least heard of them. But mind mapping can be a great study tool as well. You can make your own mind map on paper, or use the many tools available online. Color coding the map also strengthens your memory.

To make a mind map, start with a central theme or specific subject of study. Next, draw out some associations, or ideas related to your central theme. For example, for a WWII mind map, you might write out “Allied Powers” or “Europe.” Finally, draw out specific sub-associations, such as names, events or dates. For the association “Allied Powers,” you could write “Great Britain” or “the United States.”

Something to keep in mind when making your mind map is to stay concise with your associations. Instead of writing out full sentences, try to sum them up using keywords. It is also best to keep the number of associations you have to seven or less (you can have more sub-associations, though) to make sure your brain is able to handle the information properly.

5. Pomodoro Technique

Another important consideration when studying is your timeframe. It is a common misconception that studying more means studying better– but that is not necessarily true. Studying for too long can make you lose focus, and an hour spent distracted is probably less useful than 20 dedicated minutes of review.

The Pomodoro Technique, developed by 1980s university student Francesco Cirillo, breaks up studying time into small intensive segments with breaks in between. A typical Pomodoro uses 25-minute focused sessions with 5-minute breaks in between and a longer 15-30-minute break after four sessions. However, you can always adjust the times to your liking, and start off easy before increasing your focused time.

The most important part of the Pomodoro practice is to have a timer that rings at each segment’s ending to keep you on track. When you’re in the studying period, you must be completely focused without distraction, or else it defeats the purpose of Pomodoro. It is also nice to have a to-do list of achievable tasks written down before you start studying.

Pomodoro timer videos with music can be found on YouTube, and online timers such as this Aesthetic Pomodoro Timer or Tomato Timer provide many customization options while also being super fun to use. (Fun fact: “pomodoro” means “tomato” in Italian, because when Cirillo first used this technique, he used a tomato-shaped timer!)

This article mentions only a few of the endless study techniques out there, and there are many more to be discovered! Take some time to try out different techniques and find which one works best. With faster and more productive ways to review, you might find the pile of notes on your table disappearing faster than you would expect. But remember to always take a breather and relax– taking care of your health is just as important as taking care of your grades.