CONTENT WARNING: The experiment discussed within this article may be disturbing to some readers, and includes topics such as emotional and physical torture. The purpose of this article is to highlight the horrifying ethical issues with such experiments, as well as inform readers about the psychological power of the situation, which can drive people to do horrible things. Reader discretion is advised.

The campus of Stanford University in California on the morning of August 14, 1971 was quiet.

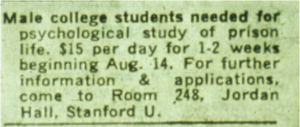

But, on message boards posted around the school, in hallways, cafeterias and dorms, an innocuous message remained posted:

“Male college students needed for psychological study of prison life. $15 per day for 1–2 weeks beginning Aug. 14. For further information and applications, come to Room 248, Jordan Hall, Stanford U,” read the poster.

In total, 71 college men – most of them cisgender male, white Stanford University students – responded. After a series of interviews and personality tests to screen for factors like psychological problems, medical disabilities and previous criminal history or drug abuse, 24 college students (whom the researchers deemed mentally fittest for the experiment) were eventually selected to earn $15 per day (in today’s money, about $120 per day) for participating in a simple psychological study for two weeks.

The purpose of this experiment? To explore the power of what Yale psychologist Phillip Zimbardo called “roles,” the social instructions that drive human social behavior, by observing how prison “guards” with perceived power would treat the “prisoners” under their jurisdiction. Zimbardo’s colleagues in the U.S. Navy also wanted to see how the conditions of a prison affected psychological dispositions to self-restraint, violence, obedience and more.

In what would eventually become one of the most infamously groundbreaking and unethical experiments in all of modern psychology, Zimbardo and his colleagues would have to abruptly end their two week study short after only six days of testing due to ethically, morally and scientifically concerning observations about the nature of human interaction.

Once all 24 participants were chosen, experimenters flipped coins to randomly assign them into two groups of twelve each. Half of the participants were assigned to be guards and the other half were assigned to be prisoners. The crucially important purpose of the coin flip, as described by Zimbardo himself, was to make sure there were no inherent psychological or biological differences between those assigned to be prisoners, or to be guards.

After that, researchers began setting up the experimental facility, boarding up both ends of a corridor in the basement of Stanford’s Psychology Department building. “The Yard,” as they called it, was the only place outside their cells where prisoners were allowed to walk, eat or exercise, except to go to use a bathroom down the hallway.

Zimbardo’s team, with Zimbardo himself as the designated “prison warden,” also included a former California prisoner who had served nearly seventeen years in prison and informed them about the mental, emotional, and physical aspects of being a prisoner. He also introduced them to a number of other ex-convicts and prison guards, who also helped construct the experimental environment.

To create the prison cells themselves, experimenters took the doors off of several laboratory rooms and replaced them with specially made doors with steel bars and cell numbers in order to create as accurate a prison simulation as possible. Cells were made to be purposefully small, with barely enough space to hold the researchers’ required three men per cell.

In addition, one end of the hall was fitted with a thin slit to allow video recording of the experiment. An intercom allowed researchers to secretly listen in on inmates’ conversations, as well as communicate with the prisoners via announcements. There were no windows or clocks to judge the passage of time, which notably resulted in an almost total lack of time awareness among both prisoners and guards.

On the side of the corridor opposite the cells was a small closet which became known as “The Hole,” Stanford Prison’s equivalent of solitary confinement. Roughly two feet wide and two feet deep but tall enough that a “bad” prisoner could stand up, the solitary confinement room was described by researchers as “incredibly claustrophobic” and “dehumanizing to reside in.”

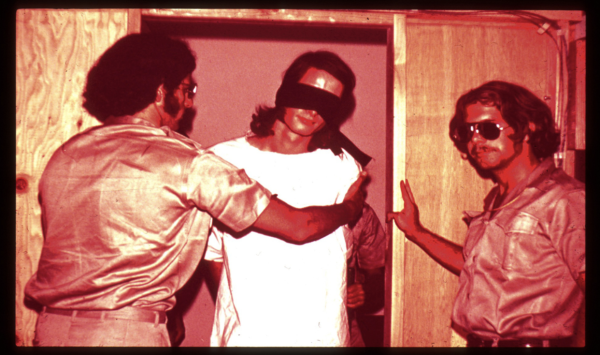

Eventually, when the prisoners’ roles were decided and the mock prison was set up, those assigned to be prisoners received “visits” from local police officers. Early in the morning, all students assigned to be prisoners were woken up by police and subsequently arrested for violating California Penal Codes 211 and 459 (clauses concerning armed robbery and burglary), searched, handcuffed and deposited into the rear of a police car.

The cars took them to the Palo Alto Police Station, where they were registered, fingerprinted, imprisoned and blindfolded – without ever being given any evidence of their supposed convictions by the law, having any legal rights read out or being informed about the arrests’ connection to the experiment they had signed up for.

Zimbardo later claimed that the nature of the arrests was to incite fear, apprehension and tension in the prisoners to accurately simulate the experience of having to go to prison for a crime. Critics have argued that these methods ignore basic scientific ethics principles such as protection from undue psychological harm and fully informed consent to experimentation.

But, the nature of the arrests themselves was far from Zimbardo’s only major violation of scientific ethics principles during the experiment.

In a presentation to Stanford University’s psychology department shortly after the study’s conclusion, Zimbardo described each prisoner’s arrival. Each prisoner was stripped naked, searched, hosed down with disinfectant and then given a uniform: a numbered gown, which Zimbardo called a “dress.” Prisoners were then fitted with a heavy chain near the ankle, and given uncomfortable rubber sandals as well as a hair cap made of women’s nylon stockings.

“Real male prisoners don’t wear dresses,” Zimbardo explained, “but real male prisoners, we have learned, do feel humiliated, do feel emasculated, and we thought we could produce the same effects in a short period of time by putting men in a dress without any underclothes.” The stocking caps were comparable to shaving the prisoner’s heads. Indeed, many prisoners immediately began acting extremely humiliated and uncomfortable directly after arrival.

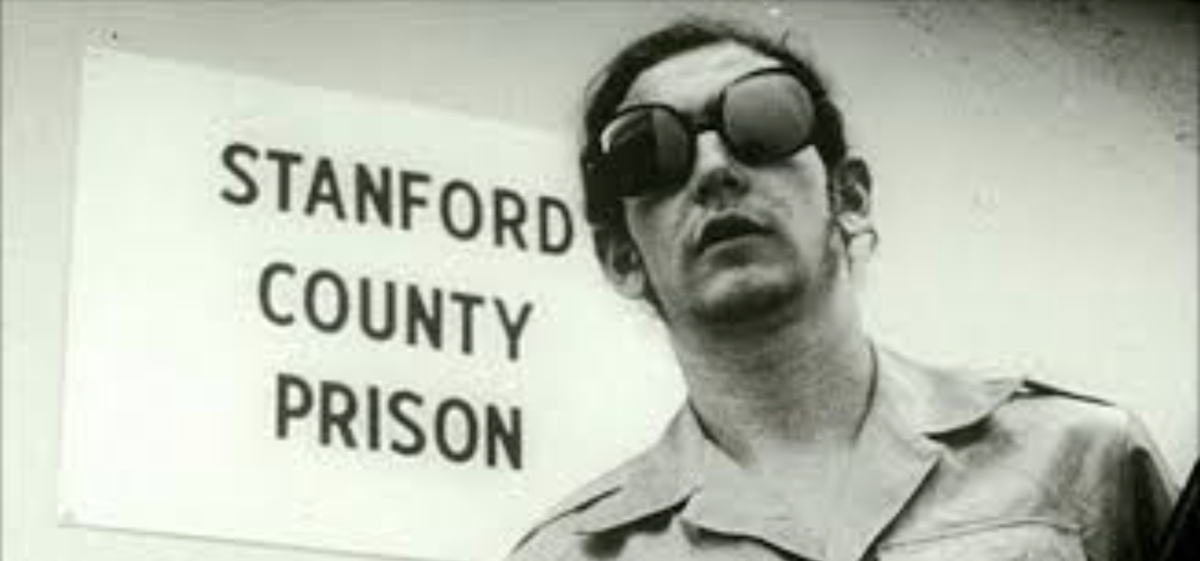

Guards were also given whistles, wooden nightsticks and mirrored sunglasses (in order to minimize eye contact with prisoners) to allow them to settle into their roles as prison managers. Guards were also asked to perform a “degradation procedure,” in which they personally administered the disinfectant hosing and were instructed to insult the prisoners to “remind them of their place within the prison system.

Prisoners were then assigned ID numbers, and guards were instructed to only refer to prisoners by ID. As with many other aspects of Zimbardo’s prison environment, the goal of these instructions was to deindividualize and dehumanize both prisoners and guards as much as possible.

Albeit quite cruel, all of the practices Zimbardo used were common in American federal prisons at the time. However, critics later pointed out that Zimbardo’s instructions for the prisoners’ treatment were much more severe than even federal prisons’ regulations were at the time.

On the first day of the experiment, guards were explicitly instructed by researchers to “be firm” with the prisoners, but to do them no physical harm. When the guards attempted to wake up inmates at 2:30 a.m. on the morning of the first night for a mandatory role call, the prisoners refused to comply with their demands and hurled insults at the guards before beginning to engage in full-blown riots and threats of physical violence.

The guards’ immediate response? Fire extinguishers.

All twelve present guards armed themselves, and began blasting rioting prisoners with freezing carbon dioxide gas. They then stripped down the organizers of the riots, removed the beds from their cells, denied other rioters food, and forced the organizers into solitary confinement for the next several hours.

One guard was recorded remarking to another, “these are dangerous prisoners, we have to be harsher to make sure this doesn’t happen again.”

Of course, not all of the guards could be present at the same time in the prison to “put down” future rebellions due to the guards’ relatively lavish living quarters being farther down the hall from the prisoners.

And so, just after the riots, the guards began to resort to psychological warfare within the second day of the experiment. They made this decision entirely on their own, without any instruction from Zimbardo – a sign that they were already letting the power of their roles enter their heads.

The next day, the guards designated one of the three cells as the “privileged” or “good” cell, in which the three protestors least-involved in the riot had their own beds, food, and hygiene supplies provided to them. In order to divide the prisoners, the guards also gave privileged prisoners special, delicious food and forced the other prisoners, who were being denied food after the riot, to watch as they ate it.

The guards then designated a “bad” cell, and began assigning sets of prisoners to each cell at total random, in an effort to turn the prisoners against each other by making them suspect one another of being informants to the guards. Riot organizers soon began to distrust those in the good cells, and the prisoners soon became wary of each other instead of organized in spirit against the guards. Such crude tactics are used even in prisons today, where real-life prison guards will pit members of a particular racial or ethnic minority against each other in order to deflect aggression away from themselves and prevent gang uprisings.

By the end of the second day, the guards had ceased to think of the prison as a simple psychological experiment. Due to the riot, the guards began to perceive the prisoners as genuinely troublesome, and began to worry for their physical safety. They started to see the prisoners as unruly and in need of discipline, and doubled down on their aggression and surveillance.

After rumors of plans for a supposed “prison break” arose on the third and fourth day, the guards escalated their punishments on prisoners even further, ordering prisoners to do hundreds of pushups at a time, forcing them to scrub toilets clean with their bare hands, relentlessly sexually harassing inmates and routinely interrupting their sleep.

When Zimbardo himself got word of plans for the prison break, he felt panicked. While personally recounting the experiments, he recalled anxiously calling the Palo Alto police department for backup (which was denied), having strategy meetings with his guards to plan out how to subdue inmates, and strategizing organized beatings of prisoners to harm their morale.

It was only after two days passed without any actual mass escape attempts that Zimbardo remarked that “it wasn’t until much later that I realized how far into my prison role I was at that point – that I was thinking like a prison superintendent, rather than a research psychologist.”

On the fifth day, prisoner number 819 began sobbing hysterically during the morning’s first role call. When approached by an on-site prison medical professional, he simply stated that he was tired of it all and that it was too much for him. He no longer referred to himself by his own name, even when it was spoken to him repeatedly. It was as if the experiment had turned him, a healthy, intelligent student at one of the most prestigious universities in the world, into an uncontrollable emotional mess.

But, the words that came out of prison number 819’s mouth paled in shock value compared to the words of his fellow prisoners.

When he was taken to a separate medical examination room to receive help, the prisoners jeered and mocked him for crying. They insulted his mental fortitude and masculinity, and began chanting in unison that he was a “bad prisoner.”

One inmate remarked to the guard that was punishing them for number 819’s actions that “because of what Prisoner 819 did, my cell is a mess, Mr. Correctional Officer.”

He and the other prisoners shouted this statement at number 819 in unison a dozen times.

His fellow prisoners, united only four days ago in mutual camaraderie against the guards, relentlessly taunted him. Even when Zimbardo offered to let him go, number 819 struggled through his tears and shook his head, saying that he was a horrible prisoner, deserved the punishment, and needed to prove himself to his fellow inmates. The conditions of the prison, which enforced strict obedience, no way to relieve punishment and sadistic torture by the guards, genuinely seemed to make him believe that he deserved the pain that was inflicted upon him by Zimbardo’s experiment.

Zimbardo eventually sent him home.

By the end of the fifth day, Zimbardo noted that the prisoners were “disintegrated, both as a group and as individuals.” There was no longer any camaraderie, “just a bunch of isolated individuals hanging on, much like prisoners of war or hospitalized mental patients.”

The guards had total control over the prison, and the prisoners stopped resisting the guards’ harsh treatments, which by then included extreme emotional, psychological, sexual and physical torture that only grew harsher with time.

This lack of resistance was later attributed to a psychological phenomenon known as “learned helplessness,” in which a person that has faced punishment multiple times for an action, such as being beaten for resisting a guard, will no longer perform that action for fear of punishment even if the consequences are removed. The prisoners’ learned helplessness convinced them that there was no escape and that resistance would only lead to further torture.

Zimbardo later remarked that “their sense of reality had shifted, and they no longer perceived their imprisonment as an experiment.”

On the sixth day, Zimbardo’s girlfriend, Christina Maslach, a prestigious Stanford psychologist herself, came to the prison to observe the prisoners alongside him. When she saw the conditions the prisoners were living in and the abject sadism that the prison guards enacted on them, she immediately ordered Zimbardo to cease the experiment on ethical grounds.

Out of the 50 or so people Zimbardo brought into the facility in six days, she was the first to question the experiment’s morality. Only after ceasing the experiment did Zimbardo sit down and think about the ethics of it all—something that he realized he did not previously consider during the experiment, due to his mock role as a prison warden.

“We had created an overwhelmingly powerful situation – a situation in which prisoners were withdrawing and behaving in pathological ways, and in which some of the guards were behaving sadistically,” Zimbardo said. “Even the “good” guards felt helpless to intervene, and none of the guards quit while the study was in progress. Indeed, it should be noted that no guard ever came late for his shift, called in sick, left early, or demanded extra pay for overtime work.”

Evidently, the experiment had deep psychological impacts on the prisoners, guards, and even the experimenters themselves. The roles that Zimbardo had initially set out to study had taken over even the researchers’ own sense of morality, ethics and compassion – a powerful and disturbing revelation.

The ethics of Zimbardo’s experiments have since been brutally analyzed by critics of his work after he published his findings in the International Journal of Criminology and Penology, the US Navy’s psychology journals, and the New York Times.

Critics argued that those who thought that they would be participating in a prison study would have significantly higher levels of aggressiveness, authoritarianism, narcissism and social dominance, and they scored lower on measures of empathy and altruism than most other people. The critics’ arguments pointed out the fact that those who would indicate interest in a prison experiment would be more likely to have personalities predisposed to engaging in violent, unethical and criminal behaviors.

In addition, Zimbardo’s accidental unwillingness to curb the guards’ violence may have implied approval of their actions in his eyes to them. It has been well-documented in the similarly ethically questionable experiments of Stanley Milgram that people will lose much of their self-control and morality if they believe they are being ordered by an authority figure, particularly a respected or reputable figure. Such experiments have offered horrifying explanations as to how otherwise ordinary German men were able to perpetrate the Holocaust, or how US soldiers tortured, maimed, desecrated and raped innocent civilians who were suspected terrorists in Abu Ghraib during the Iraq War.

Beyond that, the basic ethical guidelines of the experiment were far from sound in the first place. The amount of psychological harm inflicted upon volunteer prisoners very clearly violated one of psychology’s most fundamental experimental ethics principles: to cause no undue harm to a subject. The guards themselves also had to deal with the internal ethical consequences of their actions, which caused them stress as well.

Later emulations of Zimbardo’s experiments in Britain proved that, if guards were instructed slightly differently, such horrible outcomes did not occur. In the British replications of the experiment, guard-prisoner relationships were far more stable when the guards were simply asked to “keep the prison running smoothly” and “ensure coherency.” These findings questioned the role of Zimbardo’s instructions for the guards in their behavior, as well as the scientific basis of his experiments in the first place.

Zimbardo countered these claims by stating that prison culture (such as guards’ or inmates’ assumptions of how a prison should be run) were different between the two cultures, and that the replicated experiments were not exact copies of his design. He also argued that without obtaining informed consent, he could never have designed the experiment in the first place, and that such biases in participant selection are present in all psychological studies. Experimenting on uninformed patients against their will, he pointed out, would have been yet another ethical issue with the morality of the experiment.

In addition, he pointed out that many of his opponents argued primarily ad hominem against him, criticizing his own morals instead of the experiments’ morals. His findings clearly underscored the fact that the prison’s design had distorted his team’s perception of morality during the experiment, and that ethical issues with the experiment were not moral failings of his character but due to the power of the situation that he had created. He argued that the actions of him and his research team were, if anything, further proof as to the power of the situation on overriding morals and ethics in one’s mind.

Regardless, these experiments, alongside Zimbardo’s, have proved two things.

Firstly, ethics are fundamental. When Zimbardo’s experiments were released to the general scientific community, there was extreme backlash about the ethical implications of his experiment, and for good reason.

Zimbardo himself noted a lack of morals during the experiment’s proceedings, and noted that he too began to think of himself in the role of a prison manager instead of a researcher. After Zimbardo’s experiments became public knowledge, he testified in front of Congress and the American Psychological Association over the morals of his work. Afterwards, new international standards on experimental ethics were passed to avoid experiments like his in the future.

Second, the power of the situation. When forced into roles of prison guards or prisoners and given orders to act a certain way, human nature corrupted and broke the twenty-four men who participated in the Stanford Prison Experiments.

Twenty-four men entered the basement of the Stanford Psychology Building stable and healthy, and all twenty-four came out scarred.

Nearly all the guards deeply regretted their actions during interviews after the experiment’s conclusion, and almost all of the prisoners reported a deep psychological stress resulting from the experiment’s conditions.

Perhaps thankfully, none of the prisoners had permanent psychological damage afterwards, even the prisoner who was allowed to leave early. Prisoner number 819 later revealed that he faked the meltdown to study for his midterms, but notably still repeatedly emphasized the demeaning and horrible conditions of his treatment in the prison.

The observations that came from these experiments serve as a powerful reminder of the reality of life: that even normal, stable people can be driven to do horrible things because of the outside world’s influence on their thoughts. Additionally, the environment plays a crucial role in our mental health, with researchers noting that previously mentally healthy prisoners experienced hauntingly deep psychological pain during the experiments due to the environment. Researchers who evaluated the 24 participants before their selection specifically picked them because they appeared to be the most normal and mentally stable compared to the other applicants. Even ordinary, moral people can be driven to the edge.

Though Zimbardo’s work is weighty, it asks important questions about human behavior:

Can anybody become evil, violent, or prejudiced if the situation forces them to?

Can this influence be instead positive – can people be driven to be selfless and to love others?

Are we as humans naturally predisposed to such behaviors? Why?

Zimbardo’s experiments, though controversial, encourage similar philosophical, scientific, and ethical questions, as well as so much more. Findings such as his are important for figuring out why we need to ask ourselves these kinds of questions in the first place.

So, the next time you see someone acting radically, or being rude or violent or selfish, take a step back. Is that really a reflection of who they are, or just the situation that they live in?

For an in-depth analysis of the deep ethical debates over Zimbardo’s work, click here. A drama documentary called “The Stanford Prison Experiment” about the prison has come out fairly recently and info can be found here. The Stanford Prison Experiments also have a website detailing the experiments and the progress of events in the prison over the six days. The website has many photos of the experiments, but more photos can be found at stanford.edu. Videos of the experiment are also easily searchable on YouTube. All information in this article was sourced from the previous three sources.