“I had to reread that email the first time I got it,” said one Middleton High School (MHS) senior who wished to remain anonymous.

“I was confused,” senior Daniela Abell-Guzman said. The email in question was from Gust Athanas, a school counselor who has been working in the Middleton Cross Plains Area School District (MCPASD) since 2009, promoting an opportunity for recognition in The Capital City Hues newspaper. The honorees, collectively called the Hues Row of Excellence, are made up of students of color graduating high school or college in Dane County with a 3.0 GPA or above—an average grade of “B” in all of their classes. But the standards, leadership, and performative nature of the award contribute to an edition that belittles rather than uplifts students of color.

The cutoff for being a member of the Hues Row of Excellence is a 3.0 GPA. Meanwhile, the minimum GPA for Middleton High School’s Honor Roll, open to students of any race, is 3.6, while High Honors is awarded to students with a 3.8 GPA or above. The fact that we are lowering standards for students of color seems to imply that students of color aren’t able to reach the same level of excellence as white students. However, the data would suggest otherwise.

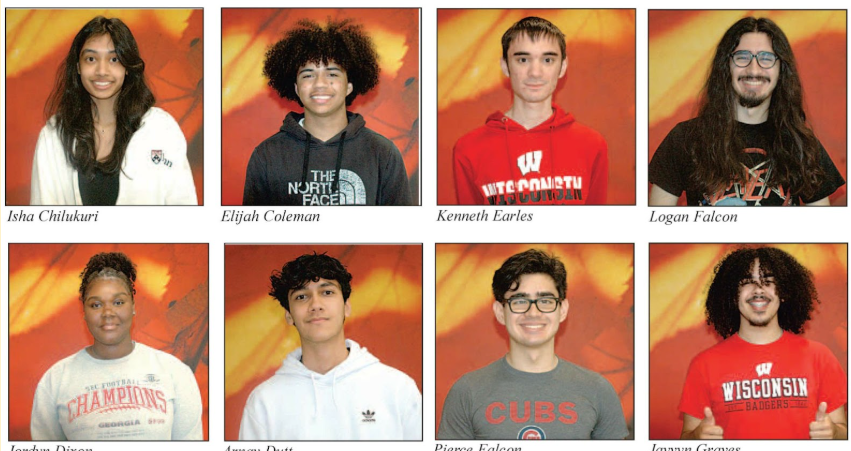

According to MHS administration, at the end of the fall 2024 semester, the average GPA for students of color at MHS was 3.29. In comparison, the standard of “excellence” set by the Capital City Hues is below average for students of color at Middleton. Nearly 30 percent of students of color at MHS achieved a cumulative GPA of 3.6 at the end of Semester 1, placing them on honor roll as well. In contrast, the Hues Row standard is set at a level where, instead of demonstrating the true achievement of students at our school, it pushes the false notion that students of color can’t achieve the same levels of scholarship white students can. Instead of this edition uplifting voices of color, it continues to belittle them.

Jonathan Gramling started The Capital City Hues newspaper after leaving his position as an editor at The Madison Times because of a change in leadership.

“I knew I’d be leaving one way or the other…and I had enough people who were still interested in my writing that I figured I would start [The Capital City Hues],” Gramling said.

He soon sold 60 percent of his newspaper to friends and people he knew, because he wanted the paper to be majority-owned by people of color. This alone starts to raise some red flags.

There is no getting around the fact that Gramling is a white person who runs an edition—and a newspaper—that claims to uplift the voices of people of color. Despite having sold most of his paper to people of color, Gramling is still editor-in-chief, controlling the vision and direction for the publication.

He is also the main reporter responsible for the Hues Row of Excellence—an initiative aiming to uplift high-achieving minority students. It seems that the power to allow diverse voices to sing still lies in the hands of privilege. Rather than allowing voices of color to be in charge, Gramling “grants” such an opportunity and thus perpetuates the idea that people of color need help from white people to have their voices heard.

Gramling disagrees with such a view.

“I attended Alcorn State University, a Historically Black College down in Lorman, Mississippi, so I got an understanding of what it was like to be, in that case, a speck of salt in a shaker of pepper,” Gramling said.

He argues that he understands what it is like to be in the minority, but while he may have been in the physical minority, he will never be subject to the systemic and implicit biases that affect the ability of racial minority groups to succeed.

The barriers that minorities face in education are not temporary hardships—they are constant discriminations that have lasting impacts. A 2022 analysis by researchers at Northwestern University found that students of color, both poor and non-poor, were subject to significantly more complaints from caregivers compared to white, non-poor students, despite the fact that there were no measured objective differences.

Furthermore, it found that these increased complaints, starting as early as preschool, affected cognitive performance in later educational years. So while Gramling’s experience may feel like being a minority in college, it cannot replicate the struggles that people of color face starting from the formative years of education and continuing to have lasting effects years later.

The fact that the organizer of this edition is not a part of the community it aims to highlight, nor does he understand the true struggles of that community, means that its execution pushes harmful stereotypes.

But what is the right way to uplift students of color? If students of color have been shown to face challenges that make it hard for them to succeed, how can we make sure to recognize and honor those struggles without being condescending?

The answer lies in the difference between recognizing and defining. We cannot, and should not, live in a “colorblind” society. So many systems of power are built to advantage groups of people and disadvantage others, solely based on the color of one’s skin. These outcomes are not due to the actions of a single “racist person,” but rather resulting from centuries of policies, practices, and injustices lived by people of color.

It is important to recognize the role that race does play in one’s life and chances of success. But recognizing such a fact does not mean that people must be defined by their skin color. I am more than just an Indian. I am a person with goals and motivations and who works hard, as any person of any race does, to get the things that I want. And yes, I may have to work harder for the same outcome, but that doesn’t mean that I want my standard to be lowered.

Another aspect of recognizing and not defining is ensuring that students of color are being truly supported rather than simply shown off. The original school email inviting students to apply to the Hues Row of Excellence went on to say that MHS has “a friendly competition” with other local high schools “to see which school can have the most students highlighted in the newspaper”. This competition hints towards a desire from the school to show off their diversity—not entirely harmful on the surface, but performative when not backed up by systems that truly support students of color.

According to the October 2024 Staffing Report by the Middleton Cross-Plains Area School District, just under 7.5 percent of certified teachers at the school identify as non-white, and just three certified teachers in the entire district, out of 659 total, are African-American. This lack of staff diversity, while MHS administration says that 35 percent of students at MHS identify as non-white, makes it feel performative to want to show off high-achieving students of color when the leaders that they see in the classroom every day don’t look like them.

The Hues Row of Excellence is not a bad idea. It is important to recognize the students of color who have overcome obstacles to still achieve great things academically. But showing off students rather than supporting them, lowering the standards to below average, and having it all be run by someone who has not experienced the struggles that he aims to combat all contribute to a flawed execution that insults students of color and their potential. Students of color do not need a special lens to shine, nor do we need a white person to give us our voice. We are people who can work hard and excel academically without crutches. We are as excellent as anyone else.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of The Cardinal Chronicle. Any content provided by our journalists is of their opinion and is not intended to malign any religion, ethnic group, club, organization, company, individual or anyone or anything.